The Selected Letters of Hannah Whitman Heyde

The Selected Letters of Hannah Whitman Heyde

Aside from his mother, Louisa Van Velsor Whitman, and his brothers George and

Jeff, Walt Whitman’s most frequent family correspondent was his youngest sister, Hannah

Louisa Whitman Heyde (November 28, 1823–July 18, 1908).

[1]

Yet information about Hannah has been scarce, mostly

limited to short mention in biographies of Whitman and in art catalogues of the

work of her husband, Charles Louis Heyde (1820–1892), a Vermont landscape painter.

Hannah, Whitman’s favorite sister, was an ongoing source of concern for the

Whitman family in the decades after her marriage to Heyde in 1852.

[2]

Hannah’s letters

provide a compelling account of domestic violence from the standpoint of the

abused woman. Verbally, psychologically, and physically abused for decades,

Hannah included descriptions of her ongoing traumatic experiences in the letters

she addressed to her mother, Louisa Van Velsor Whitman (hereafter

referred to as Mother Whitman); these letters were shared with family members. Mother Whitman was Hannah’s primary

addressee and confidant, although Hannah also corresponded with her brothers Walt,

Jeff, and George. While intimate

partner violence was recognized in mid-nineteenth-century America, it was

mostly ignored unless it escalated beyond cultural norms of silence and shame.

There were no legal remedies for battered women.

Relatively powerless and often blamed for the abuse, targets of violence

had little recourse against their abuser. In Hannah’s case, her letters became her refuge:

an alternate space where she could describe what was happening

to her. For the most part, her letters represented a safe place, but in some letters

she describes her fear of Charles reading her correspondence or discovering her in the

act of writing. Prior

to her marriage, Hannah lived at home with her parents and her brothers.

For a short while, she taught school in rural Long Island. Hannah loved to read:

she frequently expresses gratitude for the newspapers and books

that her brother Walt sent to her in Vermont.

Sewing was a favorite outlet for her creative talent, and she often describes

what she is wearing or what the latest clothing trends are in her immediate community.

After her marriage to Heyde at the age of twenty-eight, Hannah became

economically dependent on him (shortly after their marriage he refused her access to funds,

even for small household expenses). Isolated from her family

in New York, and increasingly lonely, as she mentions in her letters,

Hannah experienced

decades of mistreatment, recording the ongoing abuse in her correspondence to family members.

“The Selected Letters of Hannah Whitman Heyde”

presents an edited, annotated edition of twenty of the letters Hannah wrote.

The letters provide a

record of Hannah’s daily life and offer unique access to her point of view.

They also enrich our contextual understanding of

Whitman’s relationships with family members, and allow for a more nuanced reading

of Leaves of Grass.

This edition of Hannah Whitman Heyde’s letters enables readers to make connections

within the Whitman correspondence that has already been published, and provides

the opportunity to

understand more completely the rich interconnectivity between the Whitman

siblings and Mother Whitman. Aside from the seven volumes of Walt Whitman’s

correspondence, the Whitman family correspondence that has been

published to date includes the letters of Louisa Van Velsor Whitman; the letters

of George Whitman, brother of Walt Whitman; the letters of Thomas Jefferson

(“Jeff”) Whitman, brother of Walt Whitman; and the letters of Martha

(“Mattie”) (Mitchell) Whitman, wife of Jeff Whitman and Walt

Whitman’s sister-in-law.

[3]

Until now,

the bulk of the Whitman family correspondence that has been published consists

of letters exchanged beginning in 1860, when Walt was in Boston revising the

proofs on the third edition of Leaves of Grass, and the

Civil War years, when George was serving in the Union Army. Hannah’s letters

were written to her mother and to her brothers Walt, George, and Jeff during

the years of her marriage to Charles Heyde, from 1852 to 1892, and range in

length from four to twelve pages handwritten. More than likely Hannah received

letters not only from Mother Whitman but also from George, Jeff, and Walt,

since she refers to their letters in her correspondence. Most of the letters

that were addressed to Hannah have been lost or destroyed, some by Hannah

herself.

Heyde’s violent behavior after reading letters from the Whitman family may have motivated

Hannah to dispose of or to hide letters that she had received from her mother

and her brothers. “I had just rec’d and was reading your letter to day as Charlie came in to dinner,”

Hannah writes to Mother Whitman in spring 1856. “Charlie has not felt good

natured to day. When he read your letter he appeared quite angry. He talks so

singular when he is angry. I feel so much afraid . . ..”

[4]

Years later, in 1891, Hannah described to Walt how she

had “destroyed” the letters he had written to her: “think so very much of the

letters you’ve written me, meant to keep them long as I lived, Charly had taken

them, & I have destroyed all that he had, & he will not get hold of any

more."

[5]

Several times Hannah asked

her mother to destroy the letters she had written to her: “I know this is very

silly to write but I sho[u]ld depend certainly upon no one seeing it but you and

upon your destroying it at once, I could say much, but I think it is very bad

for me to tell or speak to you of disagre[e]able things,” Hannah writes in

1859.

[6]

Despite Hannah’s admonition, the

letters published here survived primarily because both Mother Whitman and Walt

saved the letters Hannah sent to them.

Hannah’s letters provide a glimpse into significant events in the Whitman family

during the crucial decade of the 1850s, when Whitman completed the first and

second editions of Leaves of Grass and was preparing the

third edition. The impact of the death of Walter Whitman Sr. on Hannah and on

the Whitman family in July 1855 is evident in several of Hannah’s letters from

that difficult month. While his obituary reports that he suffered from “an

exhausting illness of nearly three years,”

[7]

Walter Whitman Sr.’s death nevertheless seemed sudden to the family,

according to Hannah. Unable to attend the funeral because she had not received

word of his death (in the spring and summer of 1855 Heyde and Hannah moved

continuously from hotel to hotel and from small town to small town in rural

Vermont), Hannah felt isolated and miserable in her grief. Yet she expresses

repeated concern for her mother’s health and well-being: “I feel for you my

mother, I want very much to see you I never felt so much affection for you,” she

writes in her letter dated July 19, 1855.

[8]

Two weeks after Walter Whitman Sr.’s death, Hannah writes in an attempt to

divert her mother from her grief: “Mother dear perhaps my writing about such

trifles will take your mind a little I wish it could” (July 24, 1855).

[9]

Hannah’s letters shed light on the activities of other Whitman siblings; in addition to Walt, we learn more about Jeff,

Andrew, and George. Hannah refers to Jeff’s health in several of her letters; he

suffered from a prolonged illness in the spring of 1856. Hannah mentions the

loss of “Janey,” a young woman Jeff was perhaps courting prior to Mattie. She

comments on Andrew’s marriage in 1852 and suggests that his second child be

named George (1862), after her younger brother, George Washington

Whitman, who at the time was serving in the Union Army. Her letters add further

dimension to our understanding of the Whitman family’s concern for George’s

safety as they read the reports of casualties from the war in the

newspapers.

The abiding affection that Hannah and Walt felt for each other is evident as

well. In many of her letters Hannah expresses concern for Walt’s health. He

continued to correspond with her, often once or twice a week, after Mother Whitman’s

death in 1873, until his death in 1892, as the dates of his letters and her responses

to him in her correspondence reveal. Many of Whitman’s letters to Hannah

unfortunately were destroyed by Hannah as she admits in her letter to Whitman dated

1891.

Indeed, the last letter he wrote, dated March

17, 1892, was addressed to Hannah: “Unable to write much, Yr good letter rec’d.

$4 encd. God bless you. WW.”

[10]

As Paul

Zweig notes, “Whitman was embedded in his family, and in some ways, never left

it.”

[11]

Both of his sisters, Mary

Elizabeth and Hannah, were fond of Walt, and their affection for him was

reciprocated. Walt remained a part of his sisters’ lives, keeping in touch with

them after they were married through visits and letters. “I never in my life see

anybody so good & have so much patience with me as Walt does,” Hannah wrote

to her mother in 1866. “I dont know what makes him so good . . . its the kindness I

care for.”

[12]

Hannah knew that she

could count on Whitman for emotional support. He never failed her: he wrote

faithfully to her, sending small but sustaining amounts of money, recent copies

of newspapers and books, and letters and postcards that she treasured. Whitman

was never wealthy but he enriched Hannah’s life with his support and his steady

concern for her well-being.

In his short biography, Walt Whitman, published as an

Evergreen Profile Book in 1961, Gay Wilson Allen included a copy of the only

known portrait of Hannah, located in the Trent Collection of Whitmaniana at Duke

University; Allen’s caption under Hannah’s portrait reads, “Whitman’s favorite

sister, Hannah, Mrs. Charles Heyde.”

[13]

A revised edition of Allen’s biography was published in 1969; in this edition

Hannah’s portrait is placed next to a Civil War photograph of George Washington

Whitman.

[14]

After this, Hannah’s

image disappears entirely from ensuing Whitman biographies. In this edition of

her letters, for the first time since 1969, Hannah’s portrait is made

available.

Figure 1: Portrait of Hannah Whitman Heyde

Figure 1: Portrait of Hannah Whitman Heyde

Trent Collection of Whitmaniana, Duke University

Hannah wears a black dress with white lace half sleeves and a black shawl draped

across her shoulders. Her hair, in ringlets, is pulled back from her forehead.

Her hands are crossed in front of her and it looks as if her fingers may be

entwined. On her wrists she wears what appear to be black cloth bands. Because

she is wearing black, it is possible that this portrait was taken after her

father’s death in 1855, although no information has been uncovered about its

origin or date. Hannah gazes calmly at the camera and seems at peace; in this,

she resembles her mother. “I cant think you have grown older (as you said in one

of your letters), but mother as I grow older I can see I look more like you, not

that I look old, Oh no, but Mother often when I am combing my hair I think how

much I begin to look like you,” Hannah writes in 1858.

[15]

Later, in a letter to her brother Walt, Hannah

claimed “I don’t make a good picture,”

[16]

yet her gaze in this portrait shows serenity and self-possession, qualities

that would be severely tested during the decades of her marriage. Hannah’s

obituary published in the Vermont Bellows Falls Times

in 1908 notes that Hannah “bore a strong resemblance to her brother,” probably

because of her gray eyes, the color of her hair, and the shape of her face.

[17]

Hannah’s portrait also reveals her

attention to clothing styles and to fashion. She loved to sew; in her letters

she often refers to the shirts that she is making for Heyde. Hannah paid

attention to fabrics, to the latest styles, to what she was wearing and why.

Her choice to wear mourning after her father’s death was deliberate, because it

reflected how she felt. “I wish to have some black dresses and bonnet[s],” she

writes. “I do not like to wear such things as I have now . . . I do not like to wear

a pink or light dress and if one feels as I do, I think its right to do as you

feel,” she notes in a letter to Mother Whitman a few weeks after her father’s

death.

[18]

Often she includes a

brief description of what she is wearing so that her family could imagine how

she looked that day.

Reading Hannah’s selected correspondence provides readers with deeper insight into the

phenomenon of domestic violence in the United States during the mid-nineteenth

century. Understanding contemporary sociocultural responses to intimate partner

violence in this time period allows readers to contextualize Hannah’s individual

situation and to weigh this information against the portrayal of Hannah in

previously published biographical studies of the Whitman family. For the most

part, the characterization of Hannah that exists in the biographies of Whitman

and the critical studies of Heyde’s work has been dismissive, blaming Hannah for

the abuse she suffered and criticizing her for her supposed lack of domestic

skills. The seriousness and the complexity of Hannah’s situation have been

misconstrued by Whitman’s biographers. Justin Kaplan dismisses Hannah as

“psychotic”; David Reynolds reports that “the neurotic Hannah dressed

carelessly, never learned to cook, and kept a messy house”; Jerome Loving

concludes that Hannah was a “hypochondriac caught up in a bad marriage.”

[19]

Referring to the three letters

Hannah sent to Mother Whitman in July 1855, in which she expresses her regret

that she is so far away, Gay Wilson Allen concludes that Hannah “secretly

enjoyed her misery—subsequent letters were to reveal an unmistakable

masochistic tendency.”

[20]

As

countertestimony to these portrayals, Hannah’s correspondence with her mother,

Louisa Van Velsor Whitman, and with her brother Walt reveals that she

experienced a spiraling pattern of emotional, psychological, and physical abuse

beginning in the summer of 1855. “I feel I don’t deserve the treatment I get,”

Hannah writes in one of her letters to Walt.

[21]

For the first time, readers are provided with an alternative

perspective—Hannah’s own, in which she describes her living conditions, her

loneliness and isolation, and her response to Heyde’s violent behavior. The

evidence in the correspondence records the repeated physical, verbal, and

emotional abuse that she suffered. The Whitman family knew about her situation,

but while they expressed great concern to one another, and at times formulated

plans to remove Hannah from Vermont, they were ultimately unable to

intervene.

As late as 1888 Whitman described to Horace Traubel his concerns about Hannah:

“That whelp, Charlie Heyde, always keeps me worried about my sister Hannah: he

is a skunk—a bug . . ..He has led my sister hell’s own life: he has done nothing

for her—never: has not only not supported her but is the main cause of her

nervous breakdowns.”

[22]

It is rare

that Whitman would feel such anger toward anyone, but his characterization of

Heyde was rooted in the knowledge that his sister was the subject of physical,

psychological, and emotional abuse. Walt had always felt great affection for

Han. “I could not say that Walt was fonder of me than of the others or of any

other,” George Washington Whitman told Horace Traubel. “He was fondest of Han,

if he had any preference.”

[23]

Walt’s

fondness for his sister stemmed from their common love of books, their

experiences teaching in Hempstead, Long Island, and Hannah’s lively and cheerful

disposition, much like her mother’s, prior to her marriage. In this same

conversation with Traubel, George explained why Walt was always the sibling that

others relied on, and why Mother Whitman counted on his good judgment: “One of

the greatest things about Walt was his wonderful calmness in trying times when

everybody else would get excited. He was always cool, never flurried; would get

mad but never lose his head; was never scared....We all deferred to his

judgement, looked up to him. He was like us—yet he was different from us,

too....He was forbearing and conciliating. He was always gentle till you got him

started—always,” George notes.

[24]

Heyde was one of the few people who could get Whitman started. “It is a great

pleasure, though sometimes a melancholy one, to hear from Han, under her own

hand,” Whitman writes, to Mother Whitman.

[25]

Various poems and passages in Leaves of Grass may have

been influenced by Whitman’s awareness of Hannah’s situation and his concern for

her, specifically, section 11 of “Song of Myself” where a “lonesome” and

isolated woman looks out of her window. Reading the second edition of Leaves of Grass alongside Hannah’s letters to Mother

Whitman from winter, spring, and summer of 1856 is especially revelatory: the

placement of “Poem of Women” as the second poem in the 1856 edition underscores

Whitman’s focus on the themes of “justice” and “sympathy.” In “Poem of the Body”

Whitman added an extended catalogue to complement his 1855 assertion that “the

human body is sacred.” In the middle of the mostly joyous “Poem of the Road"

(later, “Song of the Open Road") Whitman includes a disturbing passage about “a

duplicate self,” nicely “attired,” who underneath its false exterior represents

"death” and “hell”—perhaps an allusion to Heyde’s duplicitous behavior, often

described in Hannah’s letters. Whitman ends “Poem of Remembrances for a Girl or

Boy of These States" with an assertion that “the creation is womanhood.” In

"Song of the Broad-Axe" Whitman portrays women as part of the public sphere,

processing “the streets the same as the men,” and in “Salut au Monde” he

provides a vision of the limitless potential of men and women. In these poems,

Whitman answers Heyde’s abusive dismissal of women (recorded in Hannah’s letters),

creating a

space within the boundaries of the poems where Hannah

could find affirmation and support.

Editorial Approach

Most of Hannah’s extant letters are addressed to her mother, Louisa Van Velsor

Whitman. Because Mother Whitman lived in New York while Walt lived in Washington,

DC (from 1863 to 1874), Mother Whitman may be credited with collecting and saving

the letters that were addressed to her from Hannah, but it is also possible that

some of the letters Hannah wrote to Mother Whitman were then sent to Walt or to

other family members. After Mother Whitman died in 1873, more than likely the

majority of Hannah’s letters that were in Mother Whitman’s possession were then

saved by Walt. If the letters had been returned to Hannah after Mother Whitman’s

death, Hannah might have destroyed them. Seventeen of Hannah’s letters to Walt

survive; more than likely these letters were kept by Whitman.

Hannah’s

letters to both Mother Whitman and to Walt are mixed in with each other in the

largest collection of her letters, the “Hannah Louisa Whitman Heyde Papers,

1853–1892” at the Library of Congress, which suggests that Walt was most likely the last

Whitman family member to own the composite collection of Hannah’s letters.

Since most of the letters were addressed to her, Mother Whitman most likely

kept Hannah’s letters, but after her death in 1873 the letters that Mother

Whitman had kept were probably

turned over to Whitman, whose appetite for acquiring written materials seemed boundless.

“Whitman was probably the greatest collector of his own letters,” Edwin Haviland

Miller notes, in his introduction to Whitman’s Correspondence. “As thousands

of extant manuscripts testify, few writers have shown more concern for future

renown.”

[26]

Since Whitman felt great

affection and love for Hannah, her letters more than likely became part of the collection

of materials and documents that Whitman kept.

Dr. J. Johnstone, who

visited Whitman in 1891 and 1892, described the mountain of material that

surrounded Whitman:

All around him were books, manuscripts, letters, papers, magazines, parcels tied up with string, photographs and literary material, which were piled on the table a yard high, filled two or three waste-paper baskets, flowed over them onto the floor, beneath the table, on to and under the chairs, bed, washstand, etc., so that whenever he moved from his chair he had literally to wade through this sea of chaotic disorder and confusion. And yet it was no disorder to him, for he knew where to lay his hands upon whatever he wanted, in a few moments. [27]Fortunately, Whitman was also a steadfast collector of Whitman family correspondence.

The first stage of the project was to locate all of Hannah’s extant letters. In

most instances Hannah’s correspondence is categorized as part of a larger

collection of Walt Whitman materials. Sometimes Hannah’s letters were mixed in

with other collections of correspondence, from Mother Whitman, for example, or

Charles Heyde. While more letters may exist, to date the majority of Hannah’s

correspondence may be found at the Library of Congress. The Trent Collection at

Duke University possesses seven of Hannah’s letters. The New York Public Library

(Berg Collection of English and American Literature) has two of Hannah’s

letters. These are the only two surviving letters that Hannah addressed to

recipients other than Mother Whitman and Walt; one is to her brother Jeff, and

the other, to her brother George. The Harry Ransom Center at the University of

Texas at Austin has one of Hannah’s letters, addressed to Mother Whitman and tucked

into a letter that Mother Whitman sent to Walt. Three of Hannah’s letters had

been published (in 1949) in an edited collection of Whitman correspondence, Faint Clews &

Indirections

; six of Hannah’s letters are displayed on the Walt

Whitman Archive.

[28]

For this project I had originally intended to select ten letters, thinking that

the letters I chose would adequately illustrate the range of Hannah’s experience. When it came to

the actual selection, however, ten letters did not seem sufficient.

Including twice as many letters (20) provides a greater range of

information about Hannah’s life: her first letter, written when

Hannah was newly married, expressing her homesickness; the letters that capture her

itinerant life with Heyde, moving from boardinghouse to boardinghouse in Vermont;

the letters after her father died in July 1855, when she could not be with the Whitman

family, much to her sorrow; the letters from the 1860s when George was away in

military service; her ongoing emotional connection to her mother despite the

distance between them; Hannah’s emotional descriptions of the abuse she experienced

over time; the affection, admiration, and gratitude she expresses in her letters to

her brother Walt. The twenty letters presented in this edition range from her earliest

letter to her mother (when first married to Charles and arriving in Vermont) to her

last letters, addressed to Walt. The letters are revelatory, providing a glimpse into

verbal and physical abuse from the victim’s point of view; they also attempt to conceal anguish

and suffering, as demonstrated by the numerous blotches (perhaps from tears), smudges, crossed-out

words and sentences, and sections removed with scissors. The reader is

encouraged to scrutinize Hannah’s handwritten letters as well as the transcribed

versions next to them; the handwritten texts provide remarkable testimony of Hannah’s

emotional state as she was writing and allow the reader to get a deeper sense of the woman who

exists behind the words. As the letters demonstrate, Hannah was at first bewildered

by the abuse that Charles directed at her, and somewhat shocked; as the cherished youngest daughter in the Whitman

household, Hannah was not prepared for the way Charles treated her, belittling her

abilities and physically assaulting her. As the weeks and months went by,

however, the letters provide evidence of the ways

in which she became more attuned to potentially explosive situations: guarding her

emotions; weighing her words before articulating them; assessing his moods; and

attempting to mollify his potentially explosive responses.

Once Hannah’s letters were located, the next stage of the project was to obtain a

high-quality image of each page of each letter. Since the bulk of her letters

were at the Library of Congress, reviewing the manuscripts in person provided a

more nuanced understanding of the letters as physical texts. It was clear that

the letters had been read and reread many times, perhaps by Whitman family members, from the way the pages were

folded and the texture of the paper, which in some cases had been worn smooth.

Some of the pages were torn; other pages were missing whole passages, which

Hannah (or perhaps Charles) had cut out. Page width and thickness varied. Some

letters were written in pencil, others in pen. Heyde did not provide Hannah with the

small amount of money necessary to purchase ink, so at times she had to write in pencil.

Over time, the color of the paper

and the color of ink had faded or changed. Because the letters were loosely

assembled in a folder, pages had been rearranged and separated from the original

letter, possibly by earlier researchers. Nevertheless, the letters were scanned

in the order that they were assembled in the folder at the Library of Congress.

Two rulers were used to measure the page width and length. Placing the ruler

alongside the bottom and the top of the page proved to be invaluable later in

the editing process, because measuring the page width and length provided

greater ease in matching separated pages. When scanning, all pages were copied—even the back of the page of a letter

if it had not been written on, although

this was rare, since Hannah usually filled the entire pages of her letters,

often writing upside down at the top of the page if there was a small margin, to

include a postscript.

Hannah’s letters more than likely had originally been put together in

chronological order. Because some of the pages had been separated from each

other and were out of order, several of the letters in the collection at the

Library of Congress needed to be reassembled digitally. Returning the letters to

their original form and order required a careful examination of the physical

characteristics of the document (paper used, ink or pencil) as well as the

contents of each letter. If the letter was incomplete, reviewing the fragments

and pages of letters that clearly had been separated sometimes resulted in a

match. At times, there were contextual clues present in the incomplete pieces

that provided a connection between the incomplete letter and the fragments.

Before the match could be finalized, both pieces were examined for similar

wording, phrases, or references to places and persons. Handwriting also was

helpful in piecing together the missing parts of letters. Hannah’s handwriting

changed over the decades; in the 1850s the way she shapes her words

and letters was much closer to the models in the penmanship manuals

of the 1830s and 1840s.

The paper that Hannah used was also helpful in

determining a match between pieces of an incomplete letter: the paper was often

(but not always) similar in size. The ruler measurements taken during the

scanning process became useful in this part of the process. Some of the paper

Hannah used was lined; at times she used paper available at the boardinghouses

where she stayed.

The majority of Hannah’s letters are addressed to Mother Whitman; after Mother

Whitman, Walt is her most frequent correspondent. Hannah often included

information in the header of her letters regarding time of day or month, or even

the date itself, but she did not indicate the year. The date and location of each

letter revealed the itinerant nature of the Heydes’ marriage until 1864, when

Heyde purchased a home in Burlington.

The years can be deduced

from the Whitman family events Hannah mentions in her letters: the boardinghouses,

hotels, and towns where the Heydes stayed in Vermont; the death of her father

in 1855; George’s military service during the Civil War; Jeff’s marriage and the

birth of his children; Andrew’s illness and death. Many of the letters possess a

superimposed date handwritten in red ink or in pencil in the hand of Richard

Maurice Bucke, one of Whitman’s literary executors. That Bucke had access to

Hannah’s letters, read through them, and wrote dates on them based on the

incidents mentioned in the letters lends further support to the likelihood

that Whitman had collected and kept Hannah’s letters after Mother Whitman’s death.

Usually Bucke wrote the

year, since in some instances Hannah wrote the day of the week, the month, and

the day of the month. I have placed brackets around the dates of the years to indicate

that these were not written by Hannah. Bucke

did not date all of the letters, however, so some of the letters I dated based on the

events mentioned in the letters. In all cases, the year dates are indicated in

brackets to denote either my dating of the letter or Bucke’s. The justification for the

dating of the letters as a particular year is provided in the first note to each letter.

Because there may have been some uncertainty that Whitman might have written the year date on each letter,

it was important to discern whose handwritten date was superimposed on the letters, usually

in red ink.

In order to establish that Bucke wrote the dates on

Hannah’s letters rather than Whitman, Bucke’s handwriting was compared to Whitman’s,

particularly the way they wrote numbers. For instance, the number “3” has a

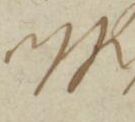

distinct shape in Bucke’s hand; see, for instance, the “3” written in red on

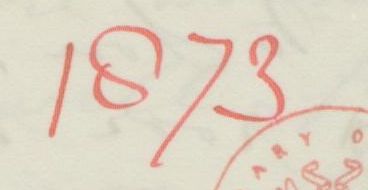

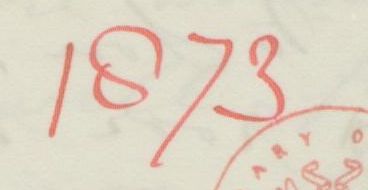

Hannah’s letter from March 4, 1873:  Figure 2: Richard Maurice Bucke’s handwriting

Figure 2: Richard Maurice Bucke’s handwriting

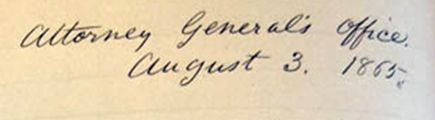

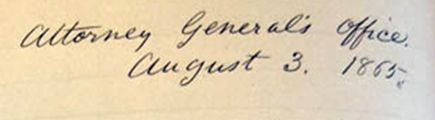

Figure 3: Walt Whitman’s handwriting

Figure 3: Walt Whitman’s handwriting

Figure 4: Richard Maurice Bucke’s handwriting

Figure 4: Richard Maurice Bucke’s handwriting

Figure 5: Walt Whitman’s handwriting

Figure 5: Walt Whitman’s handwriting

Figure 2: Richard Maurice Bucke’s handwriting

Figure 2: Richard Maurice Bucke’s handwriting

From letter of Hannah Whitman Heyde to Louisa Van Velsor Whitman, March 4, 1893, Library of Congress

Compared to the way Whitman writes the letter “3,” it is clear that

Bucke was the person who was dating Hannah’s letters.  Figure 3: Walt Whitman’s handwriting

Figure 3: Walt Whitman’s handwriting

From “Scribal Documents,” J. Hubley Ashton to William Hunter, August 3,

1865, Walt Whitman Archive

Another example is the way Whitman writes the number “5” versus the

way Bucke writes the number “5”: the above example shows that Whitman did not

connect the top bar of the letter “5,” and the lower section of the “5” was more

roundly shaped. Contrast this to Bucke’s “5,” marked on Hannah’s letter to

Mother Whitman from 1853:  Figure 4: Richard Maurice Bucke’s handwriting

Figure 4: Richard Maurice Bucke’s handwriting

From letter of Hannah Whitman Heyde to Louisa Van Velsor Whitman, 1853, Library of Congress

Finally, the way Whitman shaped the letter “W” is very distinct.  Figure 5: Walt Whitman’s handwriting

Figure 5: Walt Whitman’s handwriting

From “Correspondence,” Walt Whitman to Peter Doyle, February 23,

1872, Walt Whitman Archive

Hannah’s letter dated 1853 has the phrase “Written in Early Autumn

1853” written across the top; the “W” in this instance is clearly in

Bucke’s hand.

The next step was to date the letters. Those that had Bucke’s handwritten date on

them were carefully checked to corroborate—or to correct—the year Bucke had

written on the letter. Bucke’s dates were mostly accurate, except for a few

instances. For example, he wrote “77-83-88” on one of Hannah’s letters, above

her handwritten date of “June 16, Saturday afternoon.” Checking the calendar

years for 1877, 1883, and 1888 revealed that June 16 fell on a Saturday in 1883

and 1888, so 1877 was ruled out. Walt’s letter to William D. O’Connor in May of

1888 confirms the context of Hannah’s remarks in her letter: Whitman was

suffering from a bad head cold as well as indigestion.

[29]

Thus, Hannah’s letter of June 16 was assigned the

date of 1888. Some letters possessed no dates at all. Hannah’s letter to her

brother Walt asking urgently if George is safe was not dated. Fortunately,

Hannah had also written a letter to her mother, probably on the same day, using

this same distinct paper. Thus, Hannah’s undated letter to Walt could be dated with some

certainty with the same date as the letter to her mother, September 1862. In

some instances letters had to be dated approximately, based on events described

in other letters from the same time period. For instance, in several of her

undated letters Hannah refers to the weather and to wearing black; indeed, she

wears black dresses and bonnets so often that they wear out. “My old black silk

dress the thin one is worn out entirely Mother what shall I do, I stuck to it

long as I could,” she writes to Mother Whitman in February 1856.

[30]

Hannah refers to dental work that

she needed, and reports on her impending appointment with the dentist. At times,

the weather prevented her from leaving the hotel. Because of these details, the

date of spring 1856 was assigned to these letters, and they were placed in

sequence based on Hannah’s descriptions of the seasons, her mourning attire, and

the progress of her dental work.

All the letters in this selected edition were written by Hannah Whitman Heyde.

Seven letters are addressed to Walt Whitman, twelve letters are addressed to

Mother Whitman, and one letter is addressed to George Whitman. The word

transcriptions of the letters and the encoding of the letters were prepared from

the images of the handwritten letters. The letters have been placed in

chronological order, beginning with Hannah’s arrival in Vermont in 1852 and

ending with her last letter to her brother Walt in 1892. The first note appended

to each letter indicates the date of the letter. Images of the handwritten

letters accompany the encoded, annotated text. Hannah often indicated her

location in the heading of her letters; these were included in the transcription

and the encoding process. In most cases Hannah began a letter by addressing her

recipient as “dear.” After she finished her letter, in many instances she

included small postscripts, usually written in the top margins of the page,

upside down. Probably Hannah chose to write these passages upside down so that

the reader would know that what she had written was a postscript, and not part

of the writing on that page. Writing upside down helped the reader to find her

additional thoughts. Postscripts, notes, and afterthoughts have been placed at

the conclusion of the letter. Sometimes Hannah added interlinear words and

phrases using carets in some but not all cases to indicate the extra thoughts.

Hannah did not recopy her letters; she sent the first draft. This practice may

have been due to the cost of paper. Before she mailed the letter, in many

instances she edited what she had written by carefully rereading, adding

sentences, phrases, and words, crossing out phrases, or cutting out whole

sections of the letter. Sometimes she began a letter, put it away (or hid

it), and finished it the next day or a few days later. Some of the letters

were written hurriedly. Others were written in daily pieces and returned to over

the course of a few days, with a designation in the middle of the letter to

indicate the day of the week that she was recommencing her writing.

The letters are transcribed, encoded, and presented in as close a state as

possible to the original letter; thus the letters are presented in a diplomatic

edition. Spelling, grammatical, and punctuation errors have not been corrected.

Sentences are not always divided from each other by a period, and clauses are not

always divided by commas. Some of Hannah’s commas could be interpreted as periods;

some of her periods, as commas. The context and meaning of the surrounding text

often helped to determine whether to interpret the mark as a comma or period.

Readers can check the punctuation in the letter against my transcription and decide

whether they agree. Editing each letter called for dozens of micro-editing

decisions; my objective was to follow the context of the writing situation as

carefully as possible. In some cases, because of the sheer number of periods or

commas, it appears likely that Hannah may have simply been resting her pen on the

paper as she wrote, pausing briefly while she thought of her next sentence.

In addition to these variations in punctuation, Hannah’s paragraphing is not always

consistent. Some of the paragraphs are very long; others are short. The larger

sections of her letters are sometimes separated by a dash. Hannah’s variable

punctuation style and loose paragraphing

may be attributed to several factors. First, Hannah knew that her

addressees (her brothers and her mother) would not expect grammatically

perfect letters, so she did not need to be overly attentive to punctuation.

Second, many of her letters were written surreptitiously, because Heyde was

surveilling her correspondence to her family. In some instances Hannah had to

write her letters quickly and bring them to the post office without Heyde’s

knowledge. The transcription may assist in the reading of the handwritten

letter; in some instances Hannah’s handwriting may be unclear. Hannah commonly

misspells certain words—such as “immagine” and “disagreable.” She forms some

letters in an unconventional manner. For instance, “x” is very loosely written,

with a small space between the two halves of the letter:  Figure 6: Hannah’s “x”

Figure 6: Hannah’s “x”

Figure 6: Hannah’s “x”

Figure 6: Hannah’s “x”

From letter of Hannah Whitman Heyde to Mother Whitman, September 1853, Hannah

Louisa Whitman Heyde Papers, 1853–1892, Library of Congress

It is possible that when she wrote the “x,” Hannah was mimicking the

way her mother formed the letter “x.” As Wesley Raabe notes, Mother Whitman

“formed the letter ‘x’ with two concave strokes (like two back-to-back

parentheses rather than two crossing strokes).”

[31]

Prior to commencing the transcriptions, I devised a style guide and a statement

of editorial procedures so that my two teams of undergraduate students could

follow a similar set of instructions when transcribing and encoding. Displaying

portions of the handwritten letters on a large screen computer allowed us as a

group to decipher those places in the letters that initially seemed illegible.

Some of the pages in the letters are closely written, because Hannah usually

tried to get as much information on the page as she could when she was nearing

the end of a letter. For these passages, the large screen display was especially

helpful. Transcribing the letters into Microsoft Word documents facilitated the editing,

annotating, and encoding process. Rather than having to reread the original

handwritten images of the letters, the transcribed Word documents were far more

accessible. The transcriptions were helpful in dating the letters, because the

information within the transcriptions could be pieced together more easily.

Common threads and themes could be discerned; place names, patterns, names of

people, and events were more accessible. At times, a narrative could be pieced

together. Letters that shared common references could be read side by side. For

instance, when Hannah writes about getting her teeth fixed in the spring of

1856, her letters could be placed in a loose sequence. The Word transcriptions

also helped to facilitate the annotation process: common references and repeated

names or places could be referenced quickly. After the Word document

transcriptions were completed, the next step was to encode the documents. Weekly

meetings, with the encoding displayed on a large screen, allowed my editorial

team to present questions about the encoding process. The arduous work of

transcribing the letters into the Word documents, fortunately, facilitated the

encoding part of the process. In most instances handwriting that was difficult

to decipher did not present a difficult obstacle to the encoder; these

challenges had already been addressed and resolved by the transcribers. As

editor I oversaw the encoding of the letters by my undergraduate student

assistants, proofreading and checking the TEI transcriptions against the

original images of the letters.

The next stage of the process was annotation. Striking the proper balance between

including enough information versus including too much information about the

places and people mentioned in the letters was a delicate task. Because the

letters were to be displayed on the Internet rather than presented in print

format, I decided to treat each letter as if it were its own discrete entity.

Thus, each letter was prepared for the hypothetical reader who might view one

letter and one transcription, or jump to another letter that was not necessarily

next in the chronological sequence. References to Whitman siblings, to places,

and to Heyde’s patrons were repeated from letter to letter, with slight

variation. The information in each note was modified slightly to accommodate the

context of the letter. My primary goal was to provide helpful information about

the references in the letter for the reader unfamiliar with the material. On the

other hand, I also wanted to avoid impeding the reading experience by providing

too many notes. Hannah and Heyde traveled widely and often throughout Vermont

during the early years of their marriage, so ascertaining their location and

identifying place names by specific dates and the names of persons mentioned in

the letters could in some cases be discerned by checking the dates and locations

of Heyde’s paintings. Heyde also took shorter day trips around the towns where

they were boarding; for these he would often take the train and sketch his

painting near the tracks, or he would walk to locations, as he mentions in

several of his letters. Hannah did not accompany him on these day trips, and

spent long hours alone in her room, as she notes in several of her letters. To track down the references, I relied

heavily on regional histories of Vermont, local newspapers, ancestry websites,

and city directories to explain references to people and places. In some

instances I was able to identify a person based on likely birthdates and years of

residence in a Vermont town; in others, I could not locate information.

Material Construction of the Letters

An examination of Hannah’s handwriting reveals that she had received instruction

in cursive. In contrast, Mother Whitman did not receive instruction in

penmanship and this may be the reason why she uses the lowercase “i” throughout

her letters; executing the “I” would be a complicated maneuver for someone not

formally trained in cursive.

Figure 7: Hannah’s “I”

Figure 7: Hannah’s “I”

From letter fragment, Hannah Louisa Whitman Heyde Papers, 1853-1892,

Library of Congress

Figure 8: Mother Whitman’s “i”

Figure 8: Mother Whitman’s “i”

From letter to Walt Whitman from Mother Whitman, December 3, 1872, Walt

Whitman Archive

Undaunted by her lack of formal penmanship instruction, Mother Whitman’s

lowercase “i” endears her to the reader and provides her with a

signature style that is at once humble and intimate.

[32]

Hannah signs her name with a

capital “H” that is fairly sophisticated in its execution.

Figure 9: Hannah’s “H”

Figure 9: Hannah’s “H”

From letter fragment, n.d., Hannah Louisa Whitman Heyde Papers,

1853-1892

Figure 10: Hannah’s “W”

Figure 10: Hannah’s “W”

From letter fragment, n.d., Hannah Louisa Whitman Heyde Papers,

1853-1892

The same sophisticated execution can be seen in the way that Hannah

writes the capital letter “W,” used most often for her brother Walt.

American penmanship had evolved gradually from the copybooks used first

by the British and then developed in the American colonies in the

eighteenth century. The style of Hannah’s capital “H” suggests that

the Whitman children may have learned penmanship from a popular series

of copybooks devised by George J. Becker,

The American System of

Penmanship:

Figure 11: Becker Copybook cover

Figure 11: Becker Copybook cover

George J. Becker, The American System of

Penmanship, Series 9

Image courtesy of Pepperdine University

Special Collections

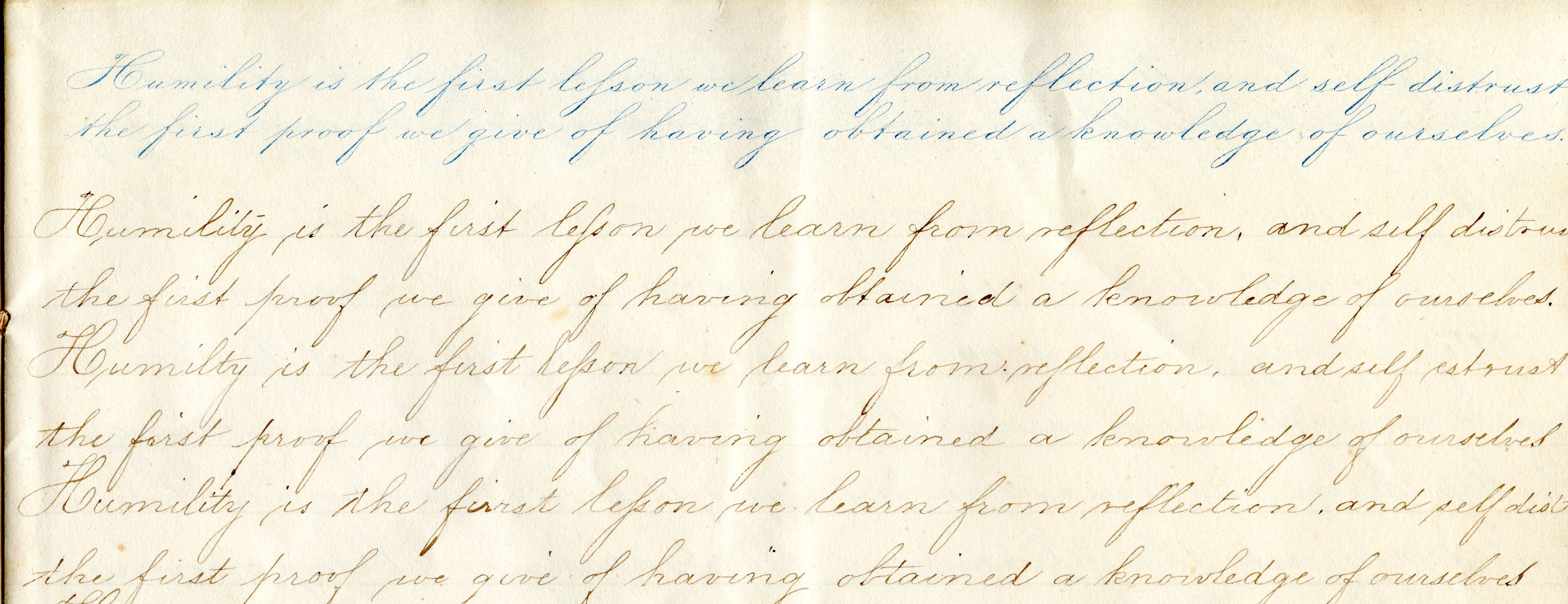

This copybook is number 9 of a series; each page consisted of copying a phrase repeatedly so that the execution of the letters

would mirror the phrase at the top of the page:

Figure 12: “Humility” exercise

Figure 12: “Humility” exercise

George J. Becker, The American System of Penmanship, Series 9, p. 7.

Image courtesy of Pepperdine University Special Collections

The loop at the bottom of Hannah’s capital “H” could be a variation of

this lesson. If the Whitman children did not learn penmanship from Becker’s

series, they may have taken lessons from one of the numerous itinerant writing

teachers who devised their own writing manuals.

[33]

Another factor in the material construction of Hannah’s letters is the invention

of the steel pen (also known as a dip or nib pen) in the early part of

the nineteenth century, manufactured after 1825 and widely used by Americans.

Prior to this, the primary writing instrument was the quill pen, “cut out of the

feather by the user” and which “lent itself to shading and thin line lettering,

but it never equalled in efficiency the springy steel pen,” Charles Carpenter

notes.

[34]

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine (1850) hails the invention of

the steel pen as consonant with the growth of a literate population by noting

that the number of those who cannot write, and therefore must make their mark,

is declining: “the proportion of those who make their marks in the

marriage-register has greatly diminished since 1844.”

[35]

Hannah writes most of her letters in ink using a

steel pen; in some cases her letters are written in pencil. “Dear Mother, I am

just going to write a line with a pencil,” she writes in March of 1856, “I

expect you must think my letters carelessly written this time I have no ink.”

[36]

Hannah runs out of ink or does

not have ink in the house fairly often. Early in their marriage, Hannah reported

that Heyde did not provide her with funds for household expenses, so it is

possible that she was not able to purchase ink when she needed it. During her

visit to Burlington in 1865 Mother Whitman used a pencil: “i would not write with a pencil if i had pen and ink but

i must write with something,” she tells Walt.

[37]

In the late 1830s, railroad lines were built throughout Vermont. Prior to this,

Burlington relied on ferries and steamboats that crossed Lake Champlain, or

stagecoaches, for transportation.

[38]

Two railroad companies established lines in Burlington: the Rutland &

Burlington Railroad, with rail lines south and east to Bellows Falls as part of

a route to Boston, as well as lines to Bennington and then on to Troy and New

York.

[39]

Hannah refers to the

Rutland Railroad and to one of its builders, Mr. Thomas Hawley Canfield, in

several of her letters; Mother Whitman took the train from New York to Troy when

she visited Hannah in 1865. The second railroad company was the Vermont Central

Railroad, known as the “Green Mountain Route,” which ran from southern

Connecticut to Montreal, Quebec. More than likely this was the train route that

Charles Heyde took when he went to Ottawa in 1862. The train lines in and out of

Burlington and the small towns in Vermont where they stayed allowed Heyde to

leave town for the day, sketch a scene not too far away, and return by evening.

One of Heyde’s first studios in Burlington was located in the Rutland and

Burlington Depot, with train tracks that ran alongside Lake Champlain. In her

letters Hannah often refers to Heyde being at the “Depot.”

Railway networks also allowed for the efficient delivery of mail to Burlington.

Prior to the railroads, mail and newspapers were delivered to rural communities

by steamboats and/or stagecoach.

[40]

Hannah refers to the Post Office (which she shortens to “P.O.”) in

nearly every letter. Prior to 1863, mail had to be picked up directly at the

post office or mailed directly from the post office; there was no home delivery.

In addition, postal rates in the early 1860s were reduced, so the cost of

mailing a letter was based on weight rather than distance.

[41]

For Hannah, walking to the post office to retrieve

letters or to mail letters could at times be challenging, depending on the

weather, her health, Heyde’s proximity and state of mind, and her ability to pay

the postage for the letters she sent to Walt and to Mother Whitman. Another

factor in the material construction of Hannah’s letters was the cost of paper;

until 1867 rags (textiles) were primarily used in paper making; the

“hollander,” or rag engine (invented in 1710), beat rags into a pulp.

[42]

The technology of producing paper

continued to improve during the nineteenth century, so that by 1850 reams of

paper could be produced cheaply; nevertheless, paper for letter writing remained

expensive. Prices averaged about 20–25 cents per sheet; sometimes more,

depending on the fluctuations of the market and local demand.

[43]

Because of this, Hannah often tried

to include as much information as she could in her letters, often writing upside

down at the top of the page, or reducing the size of her handwriting as she came

to the last page of a letter.

Embedded Letters as a Way of Communicating

In order to keep in touch with each other, Whitman family members often included

letters from each other when writing to a third family member, commenting on the

earlier letter and creating a conversational connection between two or more

recipients. For instance, in November 1868 Mother Whitman enclosed a letter she

had received from Hannah when she wrote a letter to Walt (see Hannah’s

letter to Mother Whitman, November 10, 1868). In her letter to Walt she comments

on Hannah’s letter, framing it with her concerns about Hannah: “dear walt i don’t want to worry you but i thought i

would send you hannah’s letter but god only knows what will be the end

of her troubles. i have got one from him one of his ranting ones i cant tell what an awful letter it is.” Walt would

then read Hannah’s

letter alongside Mother Whitman’s letter, taking into consideration Mother

Whitman’s commentary on Hannah’s situation. Or, Walt would include in a letter

to Jeff a letter from Heyde, with news about Hannah: “Dear Brother, I have just

finished a letter to mother, and while my hand is in, I will write you a line. I

enclose in my letter to Mother, a note from Hyde —nothing in it at all, except that Han is well—and comfortably

situated.”

[44]

Sometimes they would let

each other know that they were tucking letters they had received into letters

they were writing to other family members. Whitman writes to Mother Whitman: “I

have written Han & sent her George’s last two letters from Kentucky, one I

got last week from Mount Sterling."

[45]

This brief note allowed Mother Whitman to know that George had written to Walt,

and that Hannah would now have in her possession these two letters from George.

This practice of including an earlier letter from a different family member

enabled the Whitman family members to keep in touch with one another despite

geographical separation. During the years when they were apart from one another,

letters became their sole form of interfamilial communication: they could

express concern for each other; one family member could be particularly singled

out as needing attention; and more than one pair of eyes could read, digest, and

assess information from an earlier correspondent.

In several instances, both Mother Whitman and Hannah requested that their

recipients destroy the letters they had written, but for different reasons. The

Whitman family practice of embedding letters may explain why Mother Whitman

directed that a specific letter she had written be burned, as Wesley Raabe

points out.

[46]

For instance, in her

letter to Walt dated December 15–19, 1868, Mother Whitman writes, “burn this

letter.”

[47]

If she had not made

this request, it is possible that a letter she had written that included

critical commentary about one of her children (in this case, Jeff) could

inadvertently be tucked into a letter that was addressed to the very child she

was being critical of. While she trusted that the recipient of the letter

(Walt) would do as she had asked, in fact, the letter was not destroyed

(but there is no indication that Jeff read it). Hannah also asked her

mother to destroy particular letters, but her motivations for doing so differed

from Mother Whitman’s. In some of her letters, Hannah was more explicit about

Heyde’s abusive behaviors. She asked that Mother Whitman destroy some of the

letters, perhaps because she did not want her brothers or other family members

to know the specific details about Heyde’s abusive behavior toward her. “I

should depend certainly upon no one seeing it [her letter] but you and upon your

destroying it at once,” she tells Mother Whitman.

[48]

It is possible that Hannah did not want other family

members to know about her situation because, as our contemporary understanding

of victims of abuse reveals, targets of domestic violence often feel ashamed;

they do not wish to be perceived by others as gullible, duped, or naïve.

[49]

Moreover, in addition to her concern

that family members would read her letters, it is likely that Hannah did not

want Heyde to find out that she had written about him out of fear that his abuse

of her would escalate. Mother Whitman did not destroy these letters, however;

she may have kept them so that she could confer with Walt, George, and Jeff

about Hannah’s situation.

Hannah’s Education and Writing Style

In addition to her penmanship, the sophistication of her insights and her writing

style indicates that Hannah had received formal schooling. Katherine Molinoff

reports that Hannah “had what was considered in her day an excellent education,

attending a ‘select’ school in Brooklyn and a ‘young ladies seminary’ in

Hempstead, Long Island.”

[50]

Sandford

Brown, who had known Walt Whitman when he was a young man, recalled that “‘He

kept school for a year . . . and then his sister’—Fanny, he thought—‘succeeded

him.’”

[51]

“Fanny” more than likely

is a reference to Hannah. The school year was comprised of three terms, of three

months per term; males usually taught during the fall and winter terms, and

females, during the summer terms. It is possible that Hannah taught in Hempstead

during one or more of the summer terms in the early 1840s while the Whitman

family lived in Long Island. Katherine Molinoff reports that “another bond with

Walt was that she also taught school, as he did, and at least once took over his

school on Long Island.”

[52]

If this was

indeed the case, then Hannah and Walt would have had much in common aside from

their sibling relationship.

Hannah was writing not only for a private audience of select family members but

also secretly; often she did not want Heyde to know that she was

writing letters. This need for secrecy affected her style of writing. She omits

periods and instead runs sentences together with commas, using the comma to

indicate a pause in her thought or a change in direction or topic. Because of

this practice, some of her letters possess a breathless quality, as if she is

trying to write as much as she can, as quickly as she can. “I have no time to

say what I wish to,” she writes, in spring 1856.

[53]

The majority of her extant letters are addressed to

her mother or to her brother Walt, so more than likely Hannah felt comfortable

enough with her recipient/reader to dispense with the formal details of

grammar that would slow down her writing. She reports that she writes

surreptitiously, knowing that Heyde would want to read her letters before she

sent them in order to censor her comments: “I do not wish Charlie to see this,”

she writes on December 20, 1855.

[54]

One of Hannah’s favorite marks of punctuation is the dash, often placed at the

end of sentences to indicate that she would like to write more but did not have

the space on the page or the time to do so. Other times she would use the dash

to indicate that she could not finish a thought because it was too emotionally

charged. In one instance, Hannah describes Charlie choking her: “I said oh

Charlie you tried to choke me he said if he had killed me it was no more than I

deserved, I can never explain how I felt, I was not the least angry but so

miserable . . . but never felt so bad it appears to me as I did then and as I

often do when he is so unkind such a deathly sick faint horrid feeling—.”

[55]

There are numerous

smudges, crossed-out words, crossed out lines, and excised passages in her

letters. These revisions suggest that Hannah reread her letters, at times

carefully revising phrases, adding words in between lines, crossing out

sentences, or cutting out whole passages, underscoring the way in which her

letters both reveal and conceal information about the misery of her married

life.

Heyde controlled Hannah’s behavior through attempted surveillance of her

correspondence to her family and by reading the letters that she received from

them, often confiscating the funds and reading materials that were enclosed as

small gifts for her: “you remember how I like books on the table,” she writes to

Mother Whitman, “sometimes Charlie will take them, most all away when he is

angry, & the Book of Ruth that you gave me and Walts picture, I own. Leaves of Grass is gone."

[56]

Heyde was not able to read all her letters or to

intercept all the correspondence, however. Some of the letters from her

family arrived intact; some of her letters were written without his perusal. His

oversight, and the threat of his oversight, however, compelled Hannah to write

furtively and, at times, hurriedly. Nevertheless, before posting them, she often

reread her letters if she had time, adding words or sentences in between the lines or at

the end of the letter, writing upside down at the top of the page, or in the

margins, for clarification or

expansion of her ideas. Because of their distinct shape, some of the marks

suggest that she may

have been crying when she

wrote, and her teardrops have stained the page.

[57]

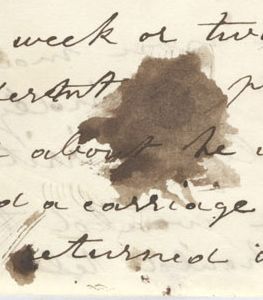

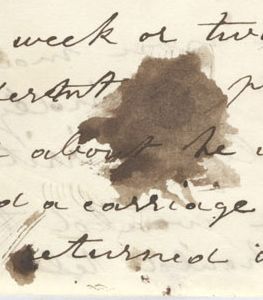

Indeed, there are stains

throughout the letters that might be interpreted as teardrops. The letters that

go into detail about the abuse are more heavily edited by Hannah; there are numerous

passages that have been crossed out, more smudges suggesting that she has been

weeping, and in some

instances whole sections of particular letters have been removed with scissors.

Hannah’s

letter from July 1856 is particularly revealing, as she goes into detail about

Heyde’s episodes of violence. In this letter, passages have been excised with

scissors by Hannah herself; it is unlikely that Heyde would have done so, since if

he had seen this letter he probably would have destroyed it.

Below is an image of what appears to be a teardrop on the second page:

Figure 13: Hannah’s teardrop

Figure 13: Hannah’s teardrop

Figure 13: Hannah’s teardrop

Figure 13: Hannah’s teardrop

Letter from Hannah to Mother Whitman, July, 1856.

Trent Collection of

Whitmaniana,

David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke

University

Surely Walt noticed the teardrop stains on the pages of Hannah’s

letters. Hannah’s tears, and her situation, may have served as inspiration for

his poem “Tears,” added to Leaves of Grass in the 1867

edition:

Tears! tears! tears! In the night, in solitude, tears, On the white shore dripping, dripping, suck’d in by the sand, Tears, not a star shining, all dark and desolate, Moist tears from the eyes of a muffled head; O who is that ghost? that form in the dark, with tears? What shapeless lump is that, bent, crouch’d there on the sand? Streaming tears, sobbing tears, throes, choked with wild cries; O storm, embodied, rising, careering with swift steps along the beach! O wild and dismal night storm, with wind—O belching and desperate! O shade so sedate and decorous by day, with calm countenance and Regulated pace, But away at night as you fly, none looking & O then the unloosen’d ocean Of tears! tears! tears! [58]The “muffled head” and “moist tears” may be a reference to Hannah, who possibly served as a model for the “ghost,” the “form in the dark, with tears,” crouching on the sand. The storm perhaps signifies her marriage to Heyde; as it moves along the beach, Whitman describes it as “dismal,” “belching,” and “desperate,” forcing from the isolated figure on the beach “sobbing tears, throes, choked with wild cries.” The silence of the night serves as cover for the “unloosen’d ocean” of tears. By day all seems “decorous” and “sedate”—perhaps a reference to Heyde’s duplicitous behavior when he first formed a friendship with Walt. The poem begins and ends in the repeated trio of “Tears! tears! tears!” punctuated dramatically with three exclamation points. The sobbing figure, “dark,” “desolate” and alone, seems beyond solace, caught up in forces beyond her control.

In the letters where she has removed

whole passages with scissors (see, for instance, her

letter to Mother Whitman dated March 1856), it is possible that

what she had written was

too disturbing, in her judgment, for her family to read. She must have gained a

small measure of comfort, however, from being able to express her feelings and

from describing what was happening to her, even if she later excised or crossed

out these too-revealing passages.

Hannah may have experienced anguish, not

knowing how much she could reveal, or should reveal, to her family, yet having

no one else to communicate with about her situation. Her primary interlocutor

was her mother, but it is possible that during the decades after her marriage

Hannah may have written many more letters to her brothers Walt, George, and

Jeff, and that very few of these letters have survived. Her brothers were reading

at least some of these letters, however; Mother Whitman more than likely

passed them along to other

family members. Surely Walt Whitman noticed the anguish and misery that his sister

was experiencing, as these letters testify.

The Epistolary Genre, Mother Whitman, and Walt

According to Mikhail Bakhtin, the epistolary form is inherently

dialogic, comprised of a writer and an addressee. The writer is constantly aware

of the ways in which the letter can be read by the recipient:

epistolary form in and of itself does not predetermine the type of discourse. In general this form permits broad discursive possibilities, but it is best suited to . . . reflected discourse of another. A characteristic feature of the letter is an acute awareness of the interlocutor, the addressee to whom it is directed. The letter, like a rejoinder in a dialogue, is addressed to a specific person, and it takes into account the other’s possible reactions, the other’s possible reply. This reckoning with an absent interlocutor can be more or less intensive. [59]An examination of the letters that Hannah addresses to her brother Walt and the letters that Hannah addresses to Mother Whitman reveals a striking difference in tone, in subject matter, and in specific details. Hannah’s letters to Walt are much shorter than her letters to Mother Whitman. The first extant letter that exists to Walt is dated 1862; by this time Hannah had experienced approximately seven years of physical, psychological, and emotional abuse. Hannah’s primary concern as reported in this letter was to obtain news about their brother, George Washington Whitman, who was serving in the Union Army. Her next letter to Walt, dated November 1868, describes her suffering during the time when her left thumb was infected. Hannah has a specific intention in this letter: she wants Walt to write to her doctor in Vermont, to thank him for his medical attention to her case. In spring 1873 Hannah writes Walt because she is worried about his health: Whitman had experienced a paralytic stroke in January 1873. The majority of Hannah’s extant letters to Walt, however, are dated after the death of Mother Whitman; it could be that if earlier letters existed they were destroyed or lost. Based on the correspondence that exists, it is clear that Hannah and Walt remained connected to each other despite the geographic distance between them. She appreciated the gifts he sent: the copies of Leaves of Grass, the small amounts of money that sustained both her and Heyde, especially in their later years, and the newspapers. The encouragement and support he expressed in his letters to her may have been the only consistent expression of kindness (aside from that of Mother Whitman) that she experienced after 1852. After her mother’s death in May of 1873, Walt became Hannah’s lifeline in terms of financial and emotional support.

While she loved her brother Walt, Hannah considered Mother Whitman her

confidant. After July 1855, she increasingly shared with Mother Whitman the

details of the abuse that she suffered at Heyde’s hands. Hannah’s closeness to

her mother was rooted in trust. Hannah begins many of her letters to Mother

Whitman with “Dear dear Mother” or with “Dear darling Mother,” salutations

that reveal her deep love and affection for Mother Whitman. In the body of the

letters, she sometimes uses the term “Mamy”; this was perhaps a common way of

addressing Mother Whitman among the Whitman siblings. In his letter dated May 8, 1865,

George refers to Mother Whitman as “Mammy"; Jeff also refers to Mother Whitman as “Mammy” in his letter dated December

8, 1872 (both letters are on the Walt Whitman Archive). The term “Mamy” or “Mammy” is not used in the salutation of the letter but

in the body of the letter as the adult child addresses Mother Whitman, usually expressing

concern for her or taking note of some emotion.

"How do you do, dear Mammy How goes it with you?" Jeff writes.

In many of the letters, Hannah takes into account

her mother’s possible responses to the violence that she reports in her letters,

and at times expresses her hesitation because she does not want to upset her mother too

deeply: “I have written to you Mother several long letters and not sent them. I

have now two by me that was written two weeks since and one written lately . . ..I

was afraid there was something in the letters about to trouble you was the cause

of my not sending them,” she writes

[60]

The abuse is reported for the first time in the extant letters beginning in

July 1855, the same month as the death of her father. “I have written very many

letters and then would feel different and would not send them,” Hannah writes.

[61]

The term she used initially was

“bothers”: “I have had some bothers, Charlie is not always very good to me but

its best to say as little about it as possible . . . when he is angry he is sometimes

very violent but I do not mind it much.” After describing Heyde’s violent

behavior, Hannah would sometimes downplay the way that the violence affects her,

wanting to maintain a cheerful tone: “its better to look on the bright side

Charlie has not been unkind to day I do not write with my mind agitated and I do

not immagine things and I do not exaggerate I have one comfort he cant be much

worse than he has been,” she writes.

[62]

Hannah’s comments in this letter may have been in response, perhaps, to

Heyde, who may have accused her of writing letters with her “mind agitated,” of

exaggerating, and of imagining “things.” Because of her phrasing, she seems to

be talking back to Heyde in a way that she could not, perhaps, in real life. Her

letter to Mother Whitman represented an alternate, safe place where she could

speak her mind without being retaliated against. The white space of the page

allowed Hannah to try to comprehend what was happening to her.

The evidence in the letters suggests that the abuse escalated in the spring of

1856, when Heyde became increasingly physically violent. She reports his

jealousy of “Mr. Hagadone, a boarder” in March 1856, and describes her reaction

to his abuse as “sometimes I mind it not so much at other times I fret untill I am sick. . . .what I cannot possibly

help I must make the best of.” A

month later, Hannah reports that she wishes she could leave Heyde, but she does

not possess the economic means to do so: “if I could only support myself someway

I hardly think I should bear so much abuse at any rate all the time.”

[63]

In this letter she reports that

Heyde abuses her verbally, telling her to pack and leave, knowing that she

cannot do so because she does not have the money to purchase a train ticket. In

this same letter, for the first time she becomes more explicit in the way she

describes Heyde’s violent behavior: “he does not hurt me much when he gets angry

he threatened to choke me to death he has struck or pushed me about some, once

he bit me a little on the shoulder more to hurt tore or wripped the sleeves of my dress that I wore but all that I care

nothing at all

about, if he would not talk so to me." Hannah was never sure what actions or

statements of hers might set off Heyde’s violent behavior. She reports that the

verbal abuse was in some ways worse than the physical abuse, perhaps because it

was unrelenting in nature: “Little things make him angry,” she writes; “there

was never a woman abused as I be I mean with talking.” Recent studies of

intimate partner violence may help us understand Hannah’s mindset.

These studies reveal that the “survivor” of “multiple traumatic

events" experiences post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety. Her

daily existence is comprised of

unrelenting negotiations with her partner, whose violent responses can be

triggered by small missteps. A sense of powerlessness may develop.

[64]

Writing letters to Mother

Whitman allowed Hannah to cope in some small way with the violence she experienced, but

the damage to her health, both physical and emotional, was lasting.

In July 1856 Hannah tells her mother that she must express her feelings to

someone: “To save my life I cannot help his getting angry. He is very violent he

is ugly. I feel as if I must sometimes speak of it to some one, and Mother I

don’t think you will mind it or feel bad about it.”

[65]

Geographically separated from her family and

relatively friendless, Hannah had no support network to turn to; she did not

attend church, and until 1864 the Heydes did not live in any one place long

enough for her to develop deep friendships or connections. Moreover, because

Heyde was a public figure in the communities they visited, he developed networks

that allowed him to marginalize Hannah and to call into question her supposed behavior, her

mental capacity, and illness, as a way of undercutting any

questions about the physical abuse. In this way, Heyde sabotaged Hannah’s

ability to report the abuse to an audience that would view her as credible.

Hannah, insulated and protected within her large family until her marriage, was

not as socially adept as Heyde and could not navigate the transient communities

in the hotels and boardinghouses where they stayed with the same facility as

Heyde could. As a way of explaining Heyde’s duplicitous behavior, Hannah reports

the following incident to her mother: “The Chamber maid and others have spokeof his being in the habit of speaking of

me to Mrs. Blodgett the

landlady. They only say he was often in her room I understood it because I once

heard him speaking or complaining to her, but did not know he was in the habit

of doing so. . . . I know that he has spoke very ill of me to her.”

[66]

Heyde’s behavior in public was pleasant and cordial; thus, he could blame Hannah

should any questions be raised about “noise or confusion or disputes.” In this

same letter she reports that “he can leave my room with the most horrid mouth

and be as pleasant as any one you ever saw to any one he meets.” Hannah’s

illnesses may have been a result of the ongoing abuse she experienced: “I know

by myself one’s mind affects the body so very much,” she tells Mother Whitman.

[67]

At times, she discloses that

she blames herself: “Every one is apt to think they are not to blame always

ready to excuse themselves. I was the cause of our living this way, then I would

have some hopes for the future.”

[68]

In

this case, Hannah may be referring to their transient lifestyle and the cost of

room and board at the hotels where they stayed. Mother Whitman’s response to

Hannah’s situation had an impact on Hannah’s ability to cope with the abuse;

Hannah must have felt that Mother Whitman reacted in a supportive manner, otherwise she would not

have continued to disclose the abuse. While Mother Whitman’s commentary on

Hannah’s situation survives in the form of correspondence with her other

children, no letters from Mother Whitman to Hannah have been located. Over time,

Heyde became increasingly critical of Mother Whitman, blaming her for Hannah’s

behavior and perhaps referencing Mother Whitman’s letters to Hannah when he

writes in a letter to Walt, “Much of this difficulty has arisen from the miserable teachings of her

mother, who enjoined upon her, when we were first married not to perform these

little services for me, which naturally would suggest themselves to a kind and

considerate wife, and endear her to her husband: Because I might be spoild, by

it.”

[69]

Heyde was reading, and in some

cases intercepting, the letters Mother Whitman wrote to Hannah. He may have