Kate Edwards Swayze (1834–62) is remembered, if at all, as the author of

Ossawattomie Brown; or The Insurrection at Harper’s Ferry (1859), a play depicting radical abolitionist John Brown’s violent involvement in the events of Bleeding Kansas and his leadership

of a failed raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, October 16–18, 1859. The play debuted as

The Insurrection at the Old Bowery Theatre in New York on December 16, 1859, and ran for three nights. Samuel French subsequently published

editions of

Ossawattomie Brown in 1859 and 1868

[1] , guaranteeing Swayze, a New York actor to whom no other publications are attributed, brief mention in the massive secondary

literature on John Brown and his cultural legacy. Discussions of

Ossawattomie Brown appear in recent books by Bruce Ronda, David S. Reynolds, and Heather Nathans, all of whom find the play—with its stock ethnic

characters, tacked-on marriage plot, emphasis on white suffering, and elision of African American characters—disappointing.

[2]

Figure 1: Bowery Theatre playbill for the December 17, 1859, production of Insurrection “by a lady of Brooklyn” (Kate Edwards Swayze)

pf TCS 65 (Bowery), Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

Four other plays attributed to Swayze under the name Kate Edwards and copied in the hand of her husband, Jason Clarke Swayze,

exist in the Manuscripts Collection of the Kansas Historical Society in Topeka, and they expand our understanding of Swayze’s

personal and professional engagement with the political events of the late 1850s.

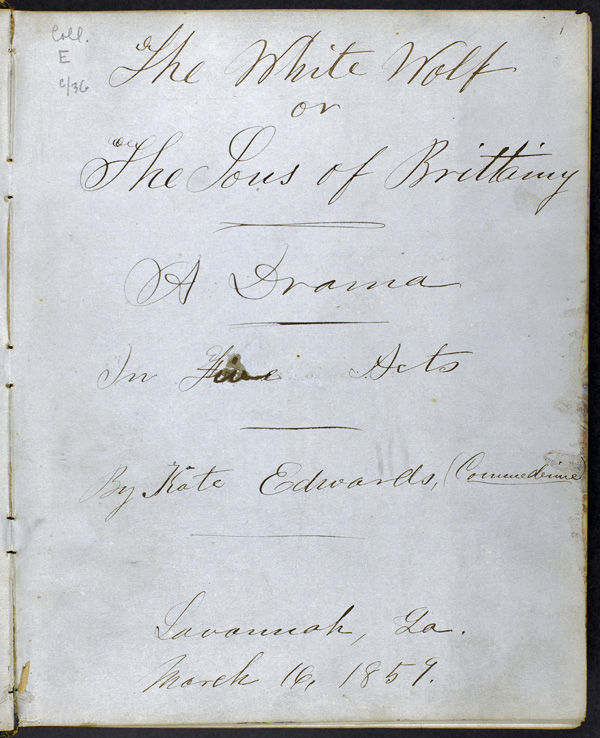

[3] The plays represent a range of common fare from the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Anglo-American stage. “The

Forger’s Daughter; a Play in Three Acts” is a sensational melodrama complete with a morally bankrupt man of leisure, impoverished

orphan, and a spectacular rescue of a young woman from a burning building. “The White Wolf; or the Sons of Brittany, A Drama

in Five Acts” is an adaptation of a French historical romance by Paul Féval, pére, about an eighteenth-century Breton revolt.

“The Play Mania; A Farce In One Act” is an Americanized version of

All the World’s a Stage (1777), a two-act farce by British playwright Isaac Jackman concerning a young woman bitten by the acting bug. And finally,

“Nigger Sweethearts” is an update of

Inkle and Yarico: An Opera, in Three Acts (1787), a popular British comic opera by George Colman the Younger.

[4] This last adaptation warrants a closer look, and not only because of its troubling title. “Sweethearts,” as we will call

the play from here on, represents a fascinating dramatic response to heightened sectional tensions over the peculiar institution—one

as striking as Swayze’s transformation of John Brown into the suffering father of a domestic melodrama.

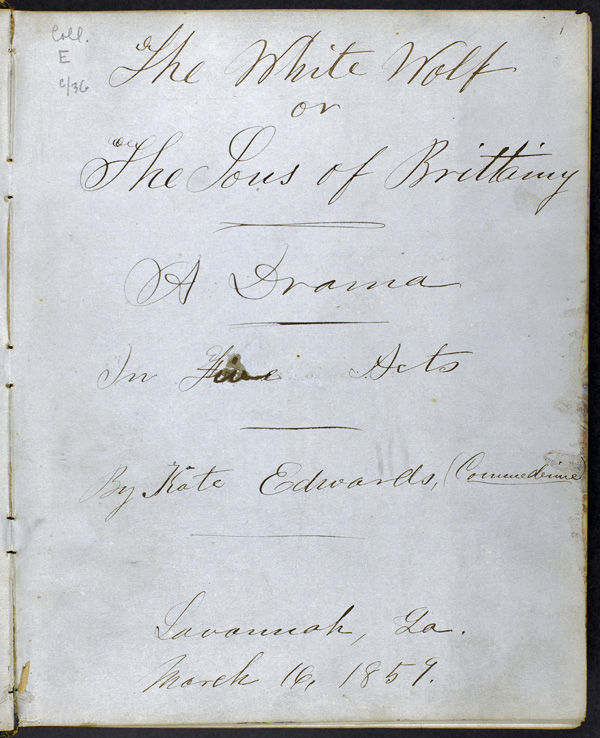

Figure 2: Title page for “The White Wolf; or the Sons of Brittany, A Drama in Five Acts”

Kate Lucy Edwards Swayze Papers, 1858B-1936. Manuscripts Collection 516, Kansas Historical Society, Topeka KS

Figure 3: Verso of title page for “The White Wolf; or the Sons of Brittany, A Drama in Five Acts”

Kate Lucy Edwards Swayze Papers, 1858B-1936. Manuscripts Collection 516, Kansas Historical Society, Topeka KS

Colman’s

Inkle and Yarico was a widely popular comic drama in the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century English-speaking world and contributed

to antislavery sentiment in Britain and the United States. It was based on a popular tale that, as Frank Felsenstein documents,

was codified by Richard Steele in the March 13, 1711, issue of

The Spectator and persisted in “well over sixty discreet versions” between 1711 and 1810.

[5] Felsenstein provides a useful synopsis of Steel’s version:

Mr. Thomas Inkle, an ambitious young English trader cast ashore in the Americas, is saved from violent death at the hand of

savages by the endearments of Yarico, a beautiful Indian maiden. Their romantic intimacy in the forest moves Inkle to pledge

that, were his life to be preserved, he would return with her to England, supposedly as his wife. The lovers’ tender liaison

progresses over several months until she succeeds in signaling a passing English ship. They are rescued by the crew, and with

vows to each other intact, they embark for Barbados. Yet when they reach the island Inkle’s former mercantile instincts are

callously revived, for he sells her into slavery, at once raising the price he demands when he learns that Yarico is carrying

his child. [6]

When Colman adapted this tale into a comedy with songs, he added characters, introduced African elements to the American setting,

omitted Yarico’s pregnancy, and provided a happy ending. As the play begins, Inkle scouts out financial opportunities on the

“Main of America” after he, his uncle Medium, fellow passengers, and the crew land there en route to Barbados. When the Brits

flee an attack by the local cannibals, Inkle and his manservant Trudge are left behind but find protection with Yarico and

her maidservant, Wowski. The hostile natives and the benevolent Yarico and Wowski are specifically described as having dark

skin and residing in a land of lions, jackals, crocodiles, baboons, and leopards, such that contemporary reviewers criticized

Colman’s seeming geographical confusion.

[7] Once Inkle, Yarico, Trudge, and Wowski land back in Barbados, Inkle determines to betray Yarico in order to fulfill his engagement

to Narcissa, the daughter of the governor, Sir Christopher Curry. Through a series of mistaken identities, Curry blesses the

union of Narcissa with her true love, Captain Campley, whom Curry believes to be Inkle, while Inkle unknowingly attempts to

sell Yarico to Curry. Enraged by Inkle’s treachery, and then told of Inkle’s true identity, Curry denounces the unfaithful

lover. As a result, Inkle has a change of heart and the play ends with the unions of all three couples and a rousing song

of celebration.

Figure 4: Title page for George Colman, Inkle and Yarico (1825)

George Colman, Inkle and Yarico: An Opera, in Three Acts (New York: Charles Wiley and H. C. Carey and I. Lea; Philadelphia: M’Carty & Davis; Boston: Saml. H. Harper, 1825), http://archive.org/details/inkleyaricooperaarno

Heather S. Nathans argues that, while Colman’s

Inkle and Yarico was generally embraced in Britain as antislavery in tenor, “its very vagueness” in terms of Yarico’s American Indian or African

identity “helped it resonate with American audiences” less inclined to such sentiments in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth

centuries.

[8] Contrasting productions of

Inkle and Yarico in 1790s Philadelphia with those in London, Jenna Gibbs concludes that “the ways theatrical narratives . . . intersected

with political discourse about slavery differed dramatically on the two sides of the Atlantic.”

Inkle and Yarico inspired poems and further versions of the tale of white treachery, many of which, but not all, reinforced the embedded antislavery

message of Colman’s original, and many theatrical productions in the United States managed largely to obscure it.

[9]

Writing about Colman’s comic opera in 1808, British novelist and playwright Elizabeth Inchbald suggested that the antislavery

message of the play would have been better secured by setting the first act in Africa.

[10] Swayze appears to have taken this observation and run with it, relocating the action of the first act to Africa, explicitly

identifying the heroine as African, and setting the remaining acts in the contemporary US South. In “Sweethearts,” Inkle becomes

Lammer, a Georgia planter who, in defiance of US law, sails to Africa with the intention of enslaving local residents, and

Yarico becomes Philis, the beautiful woman who protects him from her fellow (cannibalistic) Africans. Upon return to Savannah,

Lammer is tempted to sell his love in the slave market, only to affirm his love for her in the concluding lines.

Swayze composed “Sweethearts” not at the beginning of the nineteenth century, when slavery was often characterized—even by

slaveholders—as a necessary evil that would gradually, inevitably diminish in the United States.

[11] Rather, she adapted

Inkle and Yarico in the late 1850s when the question of slavery was threatening to tear apart the nation. According to Nathans, Colman’s comic

opera had been “out of fashion among American audiences” for over a decade by then,

[12] perhaps precisely because its critique of enslavement and endorsement of interracial marriage could no longer be dismissed

as irrelevant to the US political scene. Furthermore, Swayze penned “Sweethearts” at a time when she and her husband spent

much time in the slaveholding state of Georgia, where interracial marriage had been illegal since 1788.

[13]

This edition of “Sweethearts” explores both how and why Swayze Americanized

Inkle and Yarico in the context of the late 1850s' political and theatrical culture of the United States. We approach this through a historical

introduction, a diplomatic transcription of the play, a textual apparatus highlighting selected significant changes to Colman’s

original, and a Juxta comparison set by which the reader may further explore the differences between “Sweethearts” and an

1825 US edition of Colman’s play. Here at the outset of this edition, in order to provide the reader a broad sense of the

text of “Sweethearts,” we note seven categories of substantive differences in Swayze’s adaptation and updating of

Inkle and Yarico:

- The action of the play occurs not in “An American Forest” and Barbados but in “A Swamp in Africa” and Savannah, Georgia.

- None of the original songs are included. This does not necessarily mean “Sweethearts” was to be produced without music. Without

reference to songs or inclusion of lyrics in the manuscript, however, we cannot know what music and lyrics Swayze imagined

would appear in production.

- Throughout the play, turn-of-the-nineteenth-century Briticisms are changed to Americanisms and references to the aristocracy

and British locales are altered.

- The somewhat vaguely African-Carib features of Yarico and Wowski become the explicitly African (and occasionally minstrel)

features of Philis and Lucy. Moreover, the term “nigger” is used throughout the play in reference to people of African descent.

- The cockney manservant Trudge becomes the Irish American Riley whose language, employment, and aspirations arise from the

stage Irishman of the mid-nineteenth century.

- The Barbadian governor, Sir Christopher Curry, becomes an acquisitive Yankee businessman, Mr. Morrison, who participates in

the Southern slave trade and intends to marry off his daughter, Fanny, to a Southerner.

- The central character of Inkle is renamed Lammer and sails on a ship named the Wanderer, explicitly alluding to controversy surrounding the 1858 case of Charles Lamar, a fierce advocate of slavery from Savannah,

who partnered with the owner of a ship named the Wanderer to defy US law forbidding international slave trade.

The last of these changes points toward the primary motive behind Swayze’s brazen adaptation, and there we will begin.

Charles Lamar, the Wanderer, and Swayze’s Adaptation

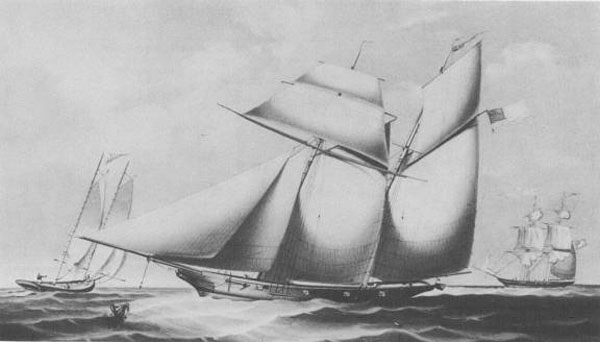

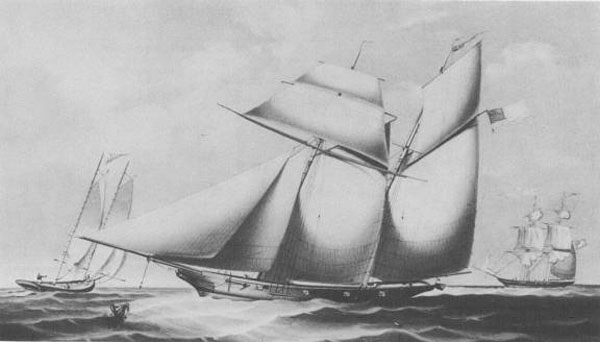

On July 4, 1858, a fleet pleasure yacht called the

Wanderer left Charleston, South Carolina, bound for western Africa where the crew intended to take on enslaved Africans for transport

back to the American South.

[14] The owner of the

Wanderer, Captain William C. Corrie, partnered with Charles Augustus Lafayette Lamar, a “fire-eater,” or Southern radical, who sought

to expand slavery and, through open defiance of federal authority and in particular the longstanding prohibition against the

importation of enslaved individuals, to hasten disunion.

[15] The

Wanderer, refitted for its illegal pursuit and helmed by Corrie, reached the Congo River in September and returned with human cargo

to Jekyll Island off the southern coast of Georgia in late November. As Erik Calonius relates, eighty of the 487 Africans

on board died during the six-week voyage, and one more died upon arrival in Georgia. The survivors of this “last confirmed

cargo of African captives to America” were quickly dispersed to regional markets.

[16]

Northern and Southern newspapers alike, with a few exceptions, condemned the

Wanderer’s voyage, but Lamar remained defiant. The

Wanderer was put up for public auction on March 12, 1859, but Lamar himself won the bid and then assaulted the competing bidder. When

the

New York Times and the

New York Herald denounced him, Lamar challenged their editors, William Raymond and Horace Greeley, to duels.

[17] Neither Lamar nor the crew of the

Wanderer were significantly punished for their actions, in part because of federal mishandling of the cases, and in part because,

Calonius argues, John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in October and subsequent trial and execution in November influenced the

court’s perception of their crime.

[18] Three sailors from the

Wanderer charged with the crime of transporting the enslaved across international waters were acquitted on November 24, 1859. When

no witnesses would testify concerning the allegation that Lamar took possession of the enslaved Africans on Jekyll Island,

the charges against him were dropped on May 28, 1860, and the charges against Corrie were likewise dropped.

[19] The brazen and unpunished crime of the men associated with the

Wanderer contributed to the heightened tensions between sections poised on the edge of civil war.

Figure 5: The Wanderer (1857)

US Naval Historical Center image via the public-domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships and Wikimedia Commons

Given the fact that the character of Lammer in “Sweethearts” takes a ship named the Wanderer to the west coast of Africa on a mission to enslave its inhabitants and the fact that the play manuscript was likely copied

in the state of Georgia, perhaps in the city of Savannah, it appears safe to say that Swayze adapted Inkle and Yarico as a direct response to the actions of Charles Lamar and his associates. Swayze’s dramatic response to the story of the Wanderer in many ways echoes her dramatic response to the capture and trial of John Brown for his leadership of the raid on Harpers

Ferry. In both cases, a fierce partisan brazenly broke federal law in order to strengthen his political cause (a Southern

fire-eater advocating the perpetuation of slavery and a radical abolitionist its overthrow, respectively) and to provoke his

opponent to action (military and judicial intervention in both cases, though with divergent results). Swayze’s plays place

the central protagonist of each event into a dramatic role that reshapes him for audience consumption. The melodramatic Ossawattomie Brown renovates Brown—whom many Northerners, even staunch abolitionists, believed to be reckless, if not altogether unhinged—into

a loving patriarch whose ill-advised actions rest on godly ideals. “Sweethearts” shoehorns the Savannah planter and political

provocateur into a well-worn character who is defined at once by avidity, treachery, remorse, and romantic love for a woman

of color.

In the antebellum period, interracial marriage “formed a powerful narrative of disruption”; to marry across racial lines was

to challenge a racial hierarchy underpinning the institution of slavery and a race-based social structure that transcended

section.

[20] Marriage between whites and people of African descent was illegal in “as many as thirty-eight states” in the nineteenth century,

and while some states repealed such laws in this period, others, including Georgia, strengthened them.

[21] The term miscegenation was coined in 1863, at the height of the Civil War, and in the words of Diana Rebekkah Paulin, “transmogrified

interracial relations into something illicit, explicit, and corporeal.”

[22] Narratives of interracial relations proliferated in the period. Defenders of slavery used the specters of interracial sex—the

predatory black man and his white female victim, as well as inferior mixed-race offspring—to support the cause. Slavery’s

opponents, including survivors of the institution, pointed to white masters’ sexual relations with enslaved women as an indication

of the institution’s unnaturalness and stirred sympathy for the enslaved through tragic narratives of doomed love between

white men and mixed-race heroines. While some radical abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison and Lydia Maria Child promoted

interracial marriage as a long-term solution to racism, they were “a small minority.”

[23] In this context, Swayze’s transformation of Lamar functions multiply: as personal insult, as political satire, and as radical

proposition. On one level, Swayze insults the honor of the white supremacist by wedding his stand-in to an African woman.

On another, she stages the abrupt conversion of the proslavery fire-eater into a radical abolitionist. And over all, Swayze

offers the courtship and marriage of Lammer and Philis as a demonstration of racial equality, though that demonstration is

hampered by the theatrical convention on which she draws.

Race and Ethnicity in the Mid-Nineteenth-Century US Theatre

Admittedly, a twenty-first-century reader easily loses sight of Swayze’s literally dramatic attack on Charles Lamar in the

midst of the racialist language and withering stereotypes of “Sweethearts.” The challenge the play poses to slavery rests

uneasily on its denigration of the physical features and culture of African people and its insistent use of the derisive n-word

to refer to people of African descent. The notorious term, commonplace in mid-nineteenth-century United States but absent

from Colman’s late eighteenth-century

Inkle and Yarico, appears not only in the title of Swayze’s adaptation, but fifteen times within the dialogue and once, perhaps most damnably,

in the stage directions.

[24] Moreover, “Sweethearts” refers to the natives of Africa as cannibals (Philis and Lucy are, of course, notable exceptions),

puns upon the dark color of Lucy’s skin and her sexual promiscuity, and presents the Irish American Riley as humorously distinguishable

from other whites in the play by his accent, Catholic faith, working-class aspirations, and amenability to an African bride.

In a play that, like

Inkle and Yarico before it, exposes slavery’s dehumanizing effects on masters as well as the enslaved, the prevalence of essentialist language

and characterization dilutes or even obscures the explicitly antislavery content.

Placed in the context of 1850s US theatre, the language and stereotypes of “Sweethearts” should come as no surprise, even

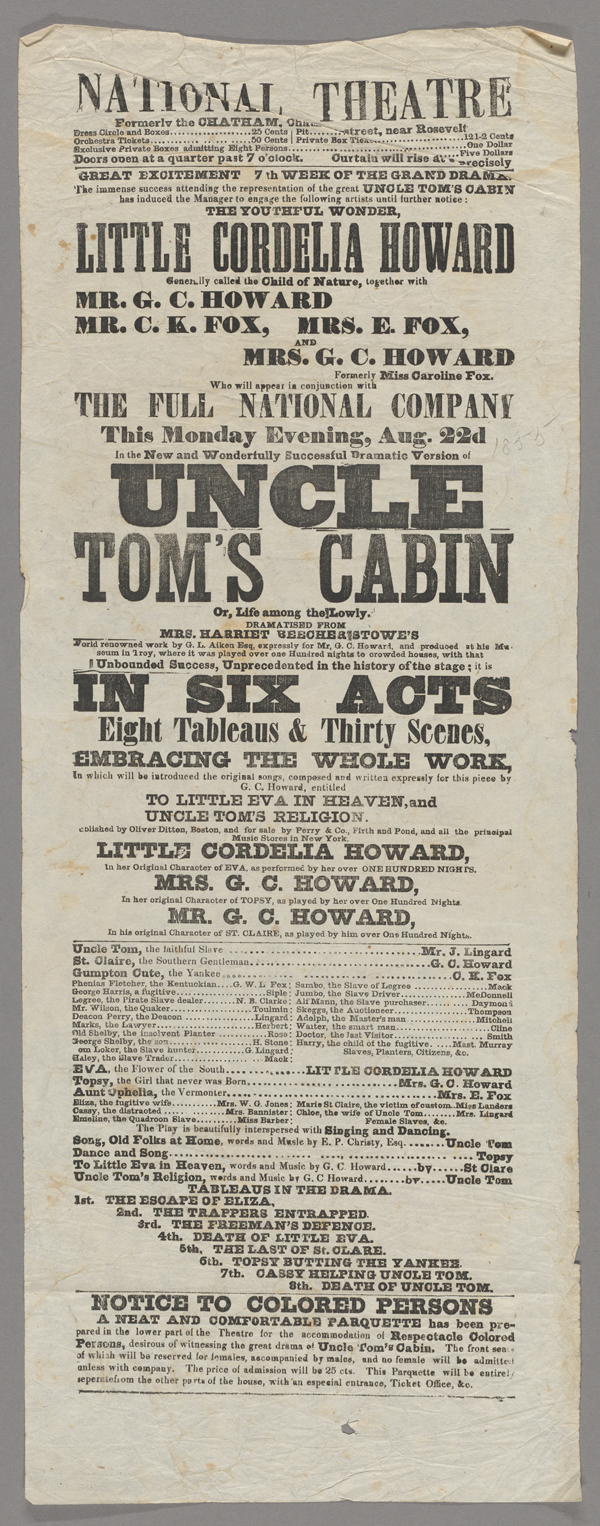

if they disappoint a twenty-first-century reader. Blackface minstrelsy was, as Eric Gardner writes, “a central piece of antebellum

American theatre” and essential to its increasing popularity in the period.

[25] Not only were there venues and traveling troupes devoted exclusively to minstrel performance, but minstrel performances

were commonly included in an evening’s theatrical lineup, and minstrel characters and set pieces made their way into standard

dramatic fare. As scholars from Eric Lott to Sarah Meer have traced, minstrelsy was essential to the staging of Harriet Beecher

Stowe’s wildly popular antislavery novel

Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851–52), and indeed should be viewed as a source text for many of the novel’s enslaved characters. Even as the parodic

elements of minstrelsy waned in the 1850s and the form “gr[ew] less sympathetic to the black figures it portrayed,” Meer argues,

minstrelsy proved difficult to extricate from abolitionist performance.

[26] Indeed, Meer concludes, the presence of the minstrel characters in William Wells Brown’s abolitionist play

The Escape; or, A Leap for Freedom (1858)—the first play published in the United States by an African American—“demonstrates the insidious ubiquity of blackface

forms in the 1850s, that they not only influenced but also helped determine the possibilities for abolitionist writing, including

some black writing.”

[27] Swayze adapted

Inkle and Yarico in the context of theatrical culture and antislavery discourse quite comfortable with the n-word and all it entailed.

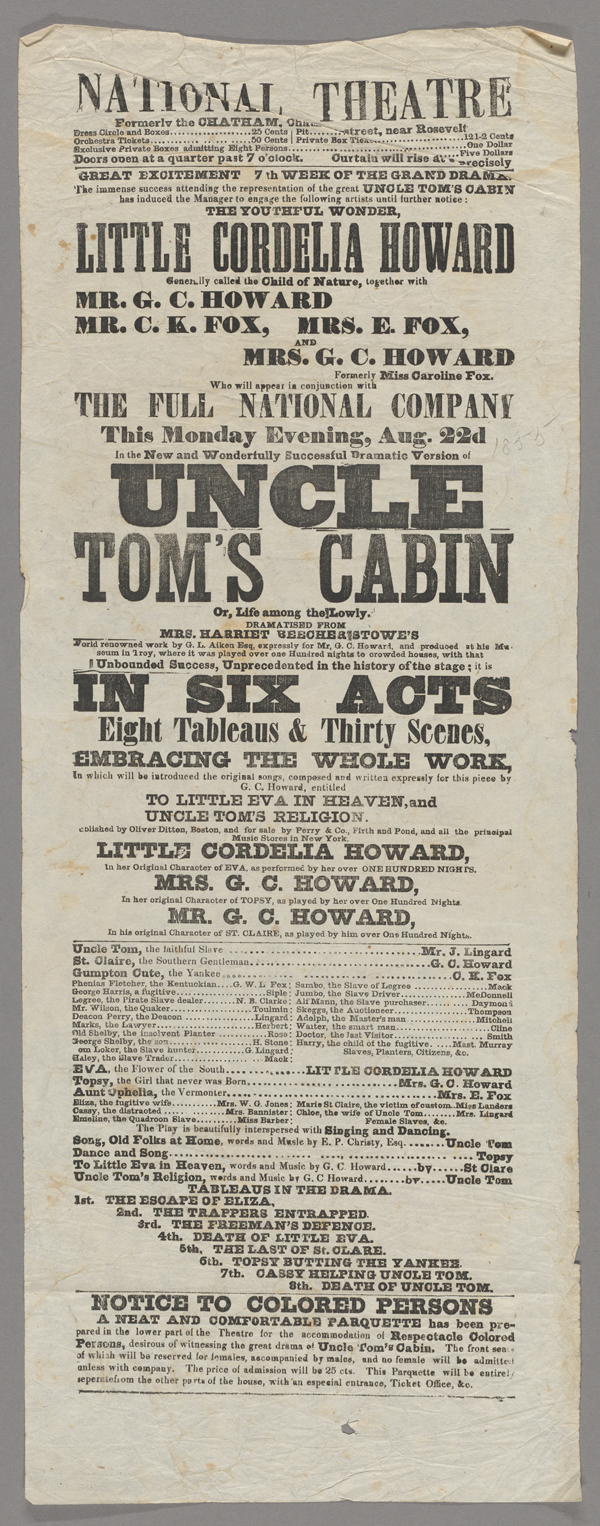

Figure 6: National Theatre playbill for the August 22, 1855, production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin

pf TCS 65 (Chatham), Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

Moreover, Swayze composed “Sweethearts” for theatre audiences regularly entertained by ethnic caricatures like Riley. As Nathans

documents, in response to the increase in Irish immigration to urban centers and the rise of nativism in the 1840s, the stage

Irishman became more comic in nature and associated with the lower class.

[28] Riley strongly resembles such characters in works such as

Irish Assurances and Yankee Modesty (1848) and

Ireland As It Is (1856), as well as antislavery dramas like Swayze’s own

Ossawattomie Brown, which contains an irrepressible Irish manservant named Little Billy. Riley’s speech is markedly Irish, as seen in its departure

from corresponding lines in

Inkle and Yarico. The Irish dialect is reflected in such choices as “sth” for “st” sounds, -in’ for -ing, and the altering of short vowel

sounds (e.g., “lave” for “leave,” “divil” for “devil,” “thim” for “them”). Moreover, exclamations like “Egad!,” “Lord!,” and

“Oh!” in Colman’s original come out of Catholic Riley’s mouth as “Howly Mother!,” “Faith!,” and “Murther!” And finally, Riley

becomes strongly associated with the African American characters of the drama as his faithfulness to Lucy never wanes and

he explicitly promotes interracial marriage as a solution to the problem of slavery. Noel Ignatiev famously writes of the

contentious and shifting relationship between Irish and African Americans in the period, noting that the two groups were perceived

as potential allies, mutually denigrated by the dominant white culture (Irish were sometimes called “white negroes” and African

Americans “smoked Irish”) and ultimately driven apart through social and economic competition. In “Sweethearts,” Riley and

Wowski do share what Ignatiev refers to as the “common culture of the lowly” as Swayze draws upon the theatrical convention

(present in

Inkle and Yarico) of pairing a set of high-born lovers with a low-born one in order to represent a powerful affiliation of African and Irish

Americans.

[29]

In addition to the stage Irishman, Swayze draws on the popularity of the stage Yankee in her transformation of Sir Christopher

Curry, the Barbadian governor, into Mr. Morrison, a businessman who has relocated from New York to Savannah to take up slave

trading. The independent and hard-headed stage Yankee was most often defined in contrast with the Irishman, the African, or

in plays by Northerners, the dissolute Southerner.

[30] The Yankee sometimes took the form of the hayseed whose naiveté was a source of humor, like Solon Shingle in Joseph Stevens

Jones’s

The People’s Lawyer (1839). In the antislavery dramatic adaptation of J. T. Trowbridge’s

Neighbor Jackwood (1857), the titular Yankee is a heroic, independent farmer. And in stage adaptations of

Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the Yankee mistress Ophelia is the image of a tireless housekeeper with no patience for others’ frivolity or laziness. While

Morrison of “Sweethearts” sticks closely to the outline of his predecessor in

Inkle and Yarico—much more so than Riley’s—the few changes Swayze does introduce emphasize his dislocation from the North and inerasable Northern

qualities of stubbornness and an irrepressible sense of right. When in act 2, scene 2, Twaddle tells him not to be “so hot!,”

Morrison responds by associating that quality with his adopted home: “Hot! Blood!—ain't I a Southerner? Ain't I a prosperous

merchant and nigger trader? Didn't I leave the fanatics of the North for my present position. Ain't my daughter going to marry

a Southerner?”

[31] The rhetorical questions prove ironic, however, as Morrison rejects slave trading, marries off his daughter to another Northerner,

and urges two young couples to embrace Northern fanaticism in the form of interracial marriage. Ultimately Morrison’s Stowe-like

belief that “it becomes every American to speak the dictates of his heart” marks him as essentially different from the representative

planter, Lammer.

Finally, the figures of Philis and Lucy resonate, respectively, with the romantic and minstrel portraits of the black female

on the US stage. Lucy, as Philis’s handmaiden and Riley’s beloved, is marked as subordinate within society and to her mistress,

and lacks the polished language and sentiment of her mistress. Lucy’s predecessor in Inkle and Yarico, Wowski, speaks pidgin English (for example, she repeatedly responds to queries with “Iss,” or yes) and openly admits to

having been wooed by countless beaus. Swayze maintains these features in Lucy, altering the nature of her rough speech by

blending the staccato delivery of Colman’s stage indigene with the dialect of the minstrel stage: “that” becomes “dat,” “then

get up” becomes “den git up,” “I tell you” becomes “I tell all bout 'em,” “beautiful” becomes “boot-ful.” Lucy is immediately

and thoroughly amenable to Riley’s advances, and as Riley puts it in a highly charged aside that comes from Colman’s original,

“If [dark complexions rubbed off like makeup] Lucy and I should have changed faces by this time.”

Philis’s relationship with her white beau, on the other hand, appears chaste from the start. She speaks with the eloquence

of a member of the natural aristocracy and acts with remarkable magnanimity. In this way, the character, whose lines are almost

wholly identical to those of Colman’s Yarico, is at once a female noble savage, most associated in the US context with Pocahontas,

who purportedly offered to sacrifice herself on behalf of the heroic swashbuckler of colonial myth, John Smith, and a darker-skinned

version of the doomed mixed-race heroine who, like Eliza Harris in

Uncle Tom’s Cabin, spectacularly risks her life to save others (in Eliza’s case, her young son).

[32] Lifted entirely from Colman’s drama but resituated in Africa and Georgia, the character of Philis brings together threads

from various American racial myths that challenge imperial violence yet also reframe that violence as necessary to the ethical

development of the nation.

As we have already suggested, interracial marriage is not simply a part of a plotline Swayze lifted from Colman but serves

a role in the play’s critique of Charles Lamar and by extension the Southern defense of slavery. Swayze’s Lammer, taken with

very little change from Colman’s Inkle, proves to be a man of sensibility who ultimately regrets betraying the woman who saved

his life and publicly acknowledges his union with her.

Inkle and Yarico ends with a joyful song, each of the newly married characters singing of their future happiness, followed by a query from

Narcissa’s disapproving maid, Patty, who asks in the final lines of the play for the audience to weigh in on interracial marriage:

Let Patty say a word—

A chambermaid may sure be heard—

Sure men are grown absurd,

Thus taking black for white;

To hug and kiss a dingy miss,

Will hardly suit an age like this,

Unless, here, some friends appear,

Who like this wedding night. [33]

Colman uses the convention of the epilogue’s request for applause to insist quite explicitly the audience join in his advocacy

of interracial marriage. The popularity of the drama suggests that applause—implicit assent—was given in the theatrical context.

The manuscript of “Sweethearts” contains no song lyrics, so we cannot know for certain which songs might have been included

in planned productions, if any were. Though Patty’s final verse does not appear in “Sweethearts,” a direct endorsement of

interracial marriage appears earlier. In act 2, scene 1, when a planter in Savannah balks at Riley’s plan to be faithful to

Lucy, the irked Irishman declares in words original to Swayze,

I'll tell ye, Misther, nigger trader, what I think ye ought to be afther doin—ye ought to import all the female niggers from

Africa and marry 'em to all our young men, and export all our young ladies to Africa to be married to the niggers there, don't

ye see, it would be followin' my example, besides dealing out equality, and blooded stock to all the world.

Riley is at once a comic character and the moral conscience of the drama, such that the planter’s response—that Riley is “not

fit to live among Christians”—appears ironic. Moreover, the resolution of the marriage plot in “Sweethearts” realizes Riley’s

vision; his proposal, initially presented as absurd, serves as the governing logic of the comedy.

With its bold validation of interracial marriage, “Sweethearts” provides a contrast with other mid-nineteenth-century cultural

productions, theatrical and otherwise, that framed interracial relations as terrifying and taboo. US literature of the 1850s

repeatedly took up the prospect of interracial relationships in two ways. First there was the figure of the tragic mulatto/quadroon/octoroon:

a mixed-race heroine who stood at the crossroads of both races, representing at once feminine purity to be rescued from the

white man’s lasciviousness and an originary sexual sin to be vanquished for the good of the whole. Second, there was the relationship

between that tragic heroine and the white hero. This plot lies at the heart of the two most famous racial melodramas of the

late 1850s, both of which were adapted from novels: Trowbridge’s

Neighbor Jackwood and Dion Boucicault’s

The Octoroon (1859). While Trowbridge’s work ends happily for the couple whose marriage crosses the white-black divide, Boucicault’s melodrama

as it was scripted for its original US audience requires the death of the titular heroine whose very existence challenges

“[t]he oppositions of slave and free, white and black.”

[34]

Figure 7: The Octoroon at the Adelphi Theatre from Illustrated London News of November 30, 1861

pf TCS 46, Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

In “Sweethearts,” the relationship between Lammer and Philis bears all the markings of this plot, and indeed, Dana Van Kooy

and Jeffrey N. Cox see

Inkle and Yarico as a forerunner to the mid-nineteenth-century racial melodrama.

[35] Though Philis is not described as mixed-race, she stands apart from all other African characters in the play with her elevated

speech, noble bearing, beauty, and generosity. Their union appears doomed in the context of a slave economy that has bred

Lammer to place profit before all else. Through her close adaptation of

Inkle and Yarico, and in a way resembling Trowbridge’s

Neighbor Jackwood, Swayze reimagines the interracial marriage in comic rather than tragic terms and uses the figure of a Yankee to achieve

the happy ending. Morrison not only shames Lammer into loyalty to Philis, he also finds a solution for their long-term happiness,

declaring in the play’s closing lines, original to Swayze: “Mr. Lammer, take an old man's advice—go—place yourself under the

jurisdiction of Horace Greeley, and you can live as happy with your nigger wife as with a white one, and she will require

a less number of servants to wait upon her.” New York State had never outlawed interracial marriage and was, after all, home

to the “fanatics” whom Morrison had fled, including Greeley. Swayze, by way of dramatic adaptation, places this stand-in for

Charles Lamar not only within an interracial marriage but also under the authority of an abolitionist whom he despised, deepening

the insult, intensifying the satire.

Despite the play’s clever use of the happily-ever-after to round out the attack on Charles Lamar, it concludes with a speech

that employs the n-word not in an act of subversion (as seen earlier in the work) but in earnestly racist humor.

[36] Morrison offers a concluding punch line dependent on the assumed servility of African people: Lammer is lucky to have a wife,

he suggests, whose racial constitution indicates she will be more than willing to do at least some of the household work herself.

“Sweethearts,” like Colman’s

Inkle and Yarico before it, assumes certain qualities inherent to the races. Yet unlike Colman’s

Inkle and Yarico, Swayze’s “Sweethearts” does not end with a romantic portrait of the noble indigene and chastened man of the world united

in love. Rather, it reverts to the keyword of American slavery and minstrelsy, insisting that despite the ground covered in

the play, the titular “nigger sweetheart” has become nothing more than a “nigger wife.”

In his recent book,

The Captive Stage: Performance and the Proslavery Imagination of the Antebellum North, Douglas A. Jones Jr. argues that in the antebellum United States, white Northerners, whether for, against, or indifferent

to slavery, “cultivated a proslavery imagination” wherein the demise of slavery was not accompanied by the expiration of racial

hierarchy.

[37] Rather, through “dramatic and theatrical representation of complaisant and submissive blackness,” white Northerners made

plain how “black people must serve the economic, moral, political, and social needs and interests of their white counterparts.”

[38] In “Sweethearts,” Riley’s unhalting acceptance of Lucy as “a black diamond among thim American wifes” is at once an updated

celebration of racial intermarriage and a jesting link between the lowly Irishman and a promiscuous black servant. The affirmation

of natural feeling that connects Lammer to Philis rests alongside a joke about Philis naturally serving as her own maid. The

racial essentialism of “Sweethearts” does not undermine its opposition to slavery; rather it reinforces a white understanding

of what the necessary relationship between whites and blacks must be in the absence of human bondage.

Theatrical Partnership of Kate Edwards and Jason Clarke Swayze

What we do know about Kate Edwards Swayze and the partner who copied her plays confirms that Jones’s reading of “complaisant

and submissive blackness” in the dramas of white Northerners—even those hostile to slavery—is quite appropriate to “Sweethearts.”

As already mentioned, Swayze’s Ossawattomie Brown has been criticized for its elision of black agency in its portrait of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, and another one

of Swayze’s manuscript dramas, “The Play Mania,” transforms working-class British characters of Jackman’s All The World's a Stage into minstrel types residing in Savannah. A closer look at the printing and political career of Kate’s husband and amanuensis,

especially after her death, illustrates the ways in which white Northern abolitionists—including those inspired to wage their

protest in the heart of a slaveholding state—denied the equality of African Americans even as they affirmed their right to

freedom.

Swayze was born Kate Lucy Edwards in London on November 24, 1834, and immigrated with her family to New York City in 1846.

[39] Under the name Kate Edwards both before and after her marriage, she appears to have acted in productions at the Old Bowery

Theatre, the Brooklyn Museum, and Wallack’s Theatre—and at other venues in and out of the city. Her turn to playwriting was

unusual but not unlikely; Amelia Howe Kritzer notes that in the antebellum period, “[t]he few women writers who wrote only

plays were generally drawn from the acting profession.”

[40]

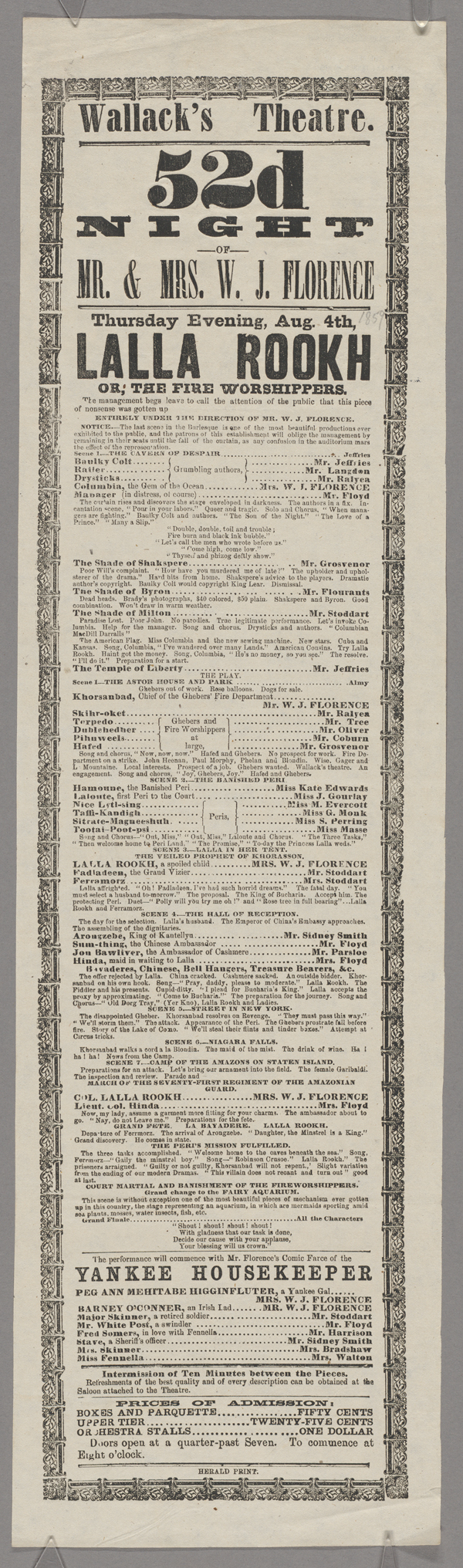

Figure 8: Wallack’s Theatre playbill for the August 4, 1859, production of Lalla Rookh starring “Miss Kate Edwards” as Hamoune

pf TCS 65 (Lyceum [Brougham’s]), Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

On June 22, 1856, Kate married Jason Clarke Swayze, a printer from New Jersey by way of Pennsylvania who shared her love of

the theatre and who tried his hand at writing fiction and drama.

[41] It appears that Jason rarely enjoyed stable employment; in 1856 alone he worked for two New York firms, lost money as a partner

in the

Saturday Evening Courier, and found fleeting success as printer for the

Venus Miscellany, a bawdy weekly overseen by an infamous purveyor of pornography, George Akarman.

[42] Meanwhile, Jason joined the Thespian Dramatic Society of the Brooklyn Museum, where Kate performed in a variety of roles.

According to their son Oscar Kepler Swayze, Kate and Jason in the first years of their marriage (1857–58) organized a theatrical

troupe under her name and toured the East and South. And while the dramatic manuscripts left behind from this period are specifically

attributed to Kate and recorded in Jason’s hand, Oscar alternately describes the plays as collaborations by his parents and

as his father’s output. He also emphasizes his parents’ practicality while touring: “Their plays not in accord with the prevailing

secession sentiment in the South, were shelved, and new plays written for the sections of their itinerary likely to take offence.”

[43] The Swayzes’ first child, Julia Harriet Swayze, was born on June 19, 1858, eighteen days after Jason copied the manuscript

of Swayze’s “Forger’s Daughter” in Clarkesville, Georgia. The following year, Jason relocated somewhat permanently to Griffin,

Georgia, where he worked for Hill and George Publishers. It is hard to determine the extent to which Kate and Julia were in

Georgia at that time, if at all. The commonness of Swayze’s stage name makes it difficult to confirm that the Kate Edwards

mentioned in the theatrical record is indeed Swayze; a review in the February 21, 1859, issue of the

Daily Morning News of Savannah announces a benefit performance that night for “Miss Kate Edwards,” and "Miss Kate Edwards" appeared in productions

at Wallack's later that year.

[44] In March of 1859, Jason copied two of Kate’s manuscript dramas, “The White Wolf” and “The Play Mania,” while in Savannah,

and by the end of that year Kate’s

Ossawattomie Brown had been staged at the Bowery Theatre and was soon published in New York by Samuel French. Jason relocated his family permanently

to Griffin in 1860, sometime after the January 19 birth of Oscar in Brooklyn.

We believe that “Sweethearts” was composed at some point between March 1859, when the auction of the Wanderer resulted in sensational press and Jason made copies of “The White Wolf” and “The Play Mania,” and May 1860, when charges

against Charles Lamar were dropped. We have yet to find firm evidence corroborating Oscar Swayze’s assertion that the manuscript

dramas were staged. It was common practice in the period for a fair copy of the playtext to be produced through the collation

of individual actor’s parts, and it is possible that “Sweethearts” and the other manuscript dramas by Swayze are the product

of such a process, headed up by Jason. He may have also copied the plays from drafts by Kate, preparing fair copies in advance

of planned publication, perhaps at his own press. What we do know about the Swayzes’ peripatetic lives suggests that, however

the surviving manuscripts were composed and compiled, Kate and Jason understood well the experience of a confirmed Yankee

embedded in Georgia society and longing for a radical North.

The last dramatic composition included in the Swayze Papers—a fragment in Jason’s hand but with no authorial attribution,

entitled “Charade, or Stone-Wall Jackson,” and set during the Civil War—hails from the mid-1861 or later.

[45] Jason purchased an interest in Hill and George and soon after published

Hill & Swayze’s Southern Railroad Guide (1862). Kate gave birth to Annie Laurie in Griffin on September 8, 1861, and died the following August. In October 1863,

Jason began to publish in Griffin the pro-union newspaper, the

Bugle Horn of Liberty, which led to mob violence.

[46] He avoided tar-and-feathering but was imprisoned in Griffin, Macon, and Atlanta before winding up in Richmond, where he was

sent to serve on the Confederate front line. Jason later claimed that he served as a spy for Sherman’s army for the remainder

of the war. Meanwhile, a family back in Griffin took care of the three Swayze children. In January 1866 Jason was appointed

an agent of the Freedman’s Bureau, but he resigned under pressure at the end of September due to complaints by local whites

who disapproved of, among other things, his attempt to form a black military company. After receiving death threats in December,

Jason decamped to Savannah, but in August 1867 he took over the Griffin newspaper the

American Union, announced it would be a Radical Republican organ, and proceeded to pen scorching attacks on Democrats, the Ku Klux Klan,

and fellow Republicans he felt were insufficiently committed to Reconstruction.

Richard H. Abbott details how, during the Reconstruction, Jason’s “hostility toward [blacks’] planter masters motivated him

as much or more than sympathy for the former slaves,” and Jason was enraged when African American colleagues and subscribers

took issue with his fiery editorials. Jason was particularly distressed by black voters’ efforts to organize and by the fact

that the position of Macon postmaster went to an African American rival. When he condemned efforts in Georgia to hold a “convention

of colored voters to consult about the political course they should set for the future,” Frederick Douglass himself declared

in the

Washington National Era, “the editor of the

Union is your enemy.” The following year Jason openly rejected social equality with African American in the pages of the

Union, referring to critical black readers as “miserable

niggers.”

[47] Swayze remained a divisive figure in the Georgia political scene until he departed with his family for Topeka, Kansas, at

the start of 1873.

[48] This is how Oscar Swayze landed in Kansas, and how, sixty years later, he came to deposit the plays in the archives of the

Kansas Historical Society.

Editorial Principles

“Sweethearts” is the sole play included in a notebook with a marbled cover and lined pages. A chunk of the cover has been

ripped off, and two pages appear to be missing from the front of the volume. The first page of the notebook is given the page

number 3, and unlike the other three manuscript dramas by Swayze, it does not include a title page with author, date, and

location. Perhaps the nature of the play, and in particular its endorsement of interracial marriage, led to the damage. Whatever

the cause, the result is that we do not have a title page indicating specifically that this is the work of Kate Edwards Swayze;

however, it has been copied in a hand and format identical to that of the other three plays attributed to Swayze and has been

attributed to Swayze by the archivist who composed the finding aid for the Kate (Lucy) Edwards Swayze Papers.

We believe this is the first time “Sweethearts” has been transcribed for public. While the four Swayze plays are mentioned

in an 1937 article by Ihn and Susan Stafford in the Kansas Historical Quarterly, neither that article nor subsequent works that cite it discuss the plays' content. In light of the neglect of "Sweethearts"

and its adaptation from a well-known British antecedent, we decided that a diplomatic transcription was in order. The transcription

includes all original spellings, omissions, and insertions but does not record line breaks within individual speeches and

omits hyphens from words divided by line breaks. Transcription was a relatively simple task; Jason Clarke Swayze’s hand is

quite clear, and in addition to the missing opening pages, the manuscript is damaged in only one other spot: the upper left-hand

corner of page 27.

Identifying which

Inkle and Yarico edition Swayze consulted proved more difficult. As Nathans points out,

Inkle and Yarico “was reprinted and adapted dozens of times in both the United States and Europe, making it virtually impossible to determine

what version of the script particular audiences might be most familiar with.”

[49] Assuming Swayze would have encountered the play through the urban theatre world, we settled on an 1825 edition published

collectively by Charles Wiley in New York, Carey and Lee and M’Carty and Davis in Philadelphia, and Harper in Boston. Comparison

with “Sweethearts” and with two other scholarly editions of

Inkle and Yarico confirmed our choice.

[50] So that readers may continue to probe Swayze’s use and transformation of Colman’s comic opera, we have provided a Juxta comparison

set of the 1825 edition (taken from Internet Archive) and “Sweethearts.”

This edition of “Sweethearts” includes endnotes that either gloss historical references in the play or comment on elements

that have been adapted from Inkle and Yarico. In addition, we have selected seven passages in “Sweethearts” for closer consideration because they represent the most substantive

changes Swayze made to the original. For each of these, framed by dotted blue lines, the reader will find a link to the corresponding

scene in the 1825 edition of Inkle and Yarico and brief commentary on the changes. In order to give the reader a sense of the songs in Colman’s opera, two of these passages

include lyrics.

Notes

1. Mrs. J. C. Swayze,

Ossawattomie Brown; or, The Insurrection at Harpers’ Ferry. A Drama in Three Acts, Standard Drama 226 (New York: S. French, 1859). The title contains one of many circulating misspellings of Osawatomie, Kansas.

A second Samuel French edition of

Ossawattomie Brown appeared in 1868. Swayze performed under her maiden name, Kate Edwards.

2. Bruce A. Ronda,

Reading the Old Man: John Brown in American Culture (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2008), 26–28, 34; David S. Reynolds,

John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 452–54; Heather S. Nathans,

Slavery and Sentiment on the American Stage, 1787–1861: Lifting the Veil of Black (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 208–11.

4. Kate Lucy Edwards Swayze Papers, 1858B-1936, Manuscripts Collection 516, Kansas Historical Society, Topeka, KS. The title

page of “The Forger’s Daughter” indicates it was copied in "Clarkesville [Georgia], June 1, 1858." It is followed by an undated

dramatic fragment (four pages) copied in a different ink and titled “Charade, or Stone-Wall Jackson.” The title page of “The

White Wolf” indicates it was copied in Savannah, Georgia, March 16, 1859, and its verso indicates it was copied by Jason Clarke

Swayze (see Figure 3). The title page of “The Play Mania” places it also in Savannah on March 24, 1859. Finally, the first

few pages of the volume in which “Sweethearts” appears have been removed, such that it lacks the title page and dramatis personae

found at the start of the other three plays. Still, similarities in appearance with the other three manuscripts and internal

textual evidence, discussed below, all suggest it too was produced in the 1858–59 period.

5. Frank Felsenstein, introduction to

English Trader, Indian Maid: Representing Gender, Race, and Slavery in the New World, An Inkle and Yarico Reader, ed. Felsenstein (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 1–2. With reference to the tale’s appearance in Richard

Ligon’s

A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados (1657), Hazel Waters calls the tale “one of the founding legends of antislavery.” Waters,

Racism on the Victorian Stage: Representation of Slavery and the Black Character (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 33.

6. Felsenstein, introduction, 2.

7. On the blending of American and African aspects in

Inkle and Yarico, see Felsenstein, introduction to

English Trader, 19; Waters,

Racism on the Victorian Stage, 34.

8. Nathans,

Slavery and Sentiment, 105.

9. Jenna M. Gibbs,

Performing the Temple of Liberty: Slavery, Theater, and Popular Culture in London and Philadelphia, 1760–1850 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014), 4. Gibbs mentions a 1790 production of the play in Philadelphia in which

Yarico appeared in American Indian garb, Britain was blamed for the introduction of the slave trade to American soil, and

the play concluded with a military spectacle that likely eclipsed the celebration of interracial marriage. Focusing less on

the ethnic or racial identity of Yarico than on the events of

Inkle and Yarico, Dana Van Kooy and Jeffrey N. Cox argue “any criticism of slavery is lost in a dramatic plot driving toward a return to traditional

family values and national honour.” “Melodramatic Slaves,”

Modern Drama 55, no. 4 (2012): 459–75.

10. Nathans,

Slavery and Sentiment, 104.

11. On the history of the “Positive Good” thesis and its ascendance in the early nineteenth century, see especially Larry

E. Tise,

Proslavery: A History of the Defense of Slavery in America, 1701–1840 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1987), chap. 5.

12. Nathans,

Slavery and Sentiment, 109.

13. On the history of anti-miscegenation laws in the United States from the colonial period through the mid-twentieth century,

see especially Peter Wallenstein,

Tell the Court I Love My Wife: Race, Marriage, and Law—An American History (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002); William D. Zabel, “Interracial Marriage and the Law” in

Interracialism: Black-White Intermarriage in American History, Literature, and Law, ed. Werner Sollors (Oxford University Press, 2000), 54–61.

14. Our account of Charles Augustus Lafayette Lamar and the

Wanderer depends upon Erik Calonius,

The Wanderer: The Last American Slave Ship and the Conspiracy That Set Its Sails (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2006), and Tom Henderson Wells,

The Slave Ship Wanderer (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1967).

15. Lamar was inspired by “demagogue” Leonidas Spratt, who argued for the reestablishment of the international slave trade

in order to bolster the peculiar institution and spur Southern secession. Convinced by Spratt, Lamar had pursued two failed

slaving ventures prior to that of the

Wanderer. Calonius,

The Wanderer, 41–49.

16. Calonius,

The Wanderer, 108, 113, 241. The international slave trade was prohibited effective January 1, 1808, by the US Congress.

17. Wells,

The Slave Ship Wanderer, 143, 48.

18. Calonius,

The Wanderer, 192.

19. Calonius,

The Wanderer, 218, 229–31.

20. Karen Wood Weierman,

One Nation, One Blood: Interracial Marriage in American Fiction, Scandal, and Law, 1820–1870 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005), 4.

21. Zabel, “Interracial Marriage and the Law,” 56.

22. Diana Rebekkah Paulin,

Imperfect Unions: Staging Miscegenation in U.S. Drama and Fiction (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), xxii. See also Sidney Kaplan, “The Miscegenation Issue in the Election

of 1864” in Sollors,

Interracialism, 54–61.

23. Weierman,

One Nation, One Blood, 5.

24. The term “negro,” but not the derisive term so prevalent in Swayze’s adaptation, appears twice in Colman’s play. For a

history of the n-word's use and its relationship to enslavement and the fight against it prior to the Civil War, see Jabari

Asim,

The N Word: Who Can Say It, Who Shouldn’t, and Why (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2007), 33–82.

25. Eric Gardner, introduction to

Major Voices: The Drama of Slavery, ed. Gardner (New Milford, CT: Toby Press, 2005), xxvii.

26. Sarah Meer, “Minstrelsy and Uncle Tom” in

The Oxford Handbook of American Drama, ed. Jeffrey H. Richards and Heather S. Nathans (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 82. See also Eric Lott,

Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), chap. 8.

27. Meer, “Minstrelsy and Uncle Tom,” 93.

28. Heather S. Nathans, “Representing Ethnic Identity on the Antebellum Stage, 1825–61,” in Richards and Nathans,

Oxford Handbook of American Drama, 106–8.

29. Noel Ignatiev,

How the Irish Became White (New York: Routledge, 1995), 41, 2. Ignatiev continues, “In antebellum America it was speculated that if racial amalgamation

was ever to take place it would begin between these two groups.”

30. Nathans, “Representing Ethnic Identity,” 101.

31. Throughout the introduction, quotations from “Sweethearts” that include insertions and strikethroughs have been silently

corrected.

32. Felsenstein notes the connection between Yarico and Pocahontas, speculating that “the story of Inkle and Yarico in the

United States was eventually submerged by the native myth of Pocahontas.” Felsenstein, introduction to

English Trader, 43. On the figure of Pocahontas in American drama of this era, see especially Laura L. Mielke,

Moving Encounters: Sympathy and the Indian Question in Antebellum Literature (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2008), chap. 8. Studies of the doomed mixed-race heroine abound. Of particular

importance is Jennifer DeVere Brody’s

Impossible Purities: Blackness, Femininity, and Victorian Culture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998).

34. Brody,

Impossible Purities, 50. Boucicault rewrote the ending of

Octoroon for British audiences, who much preferred that the heroine survive to live happily ever after with her white husband. See

also Daphne Brooks,

Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850–1910 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 33.

35. Van Kooy and Cox, “Melodramatic Slaves,” 462–63.

36. Half of the instances of the n-word fall to Riley, who is faithful to Lucy and serves as the play’s primary advocate for

interracial marriage, suggesting a somewhat subversive quality to his use of it. Indeed, the word is central to his sarcastic

response to Lammer’s treachery; having eavesdropped on Lammer as he laments his love for Philis and the confusion it has caused,

Riley sarcastically, gleefully comments for the sake of the audience, “And all for a nigger!” But for all of Riley’s wily

ways, the title and these closing lines of the play bookend the plot with a joke about interracial marriage and thus defuse

the radical suggestion at its heart.

37. Douglas A. Jones Jr.,

The Captive Stage: Performance and the Proslavery Imagination of the Antebellum North (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2014), 2.

38. Jones,

Captive Stage, 11, 19.

39. The biographical information on Swayze comes from Stafford and Stafford, “An Old Play on John Brown,” and from materials

in the Kate Edwards Swayze Papers and the Oscar K. Swayze Papers (Manuscripts Collection 83, Kansas Historical Society, Topeka,

KS), especially Jason Clarke Swayze’s daybook from 1856, the year Kate and Jason were married.

40. Amelia Howe Kritzer, “Antebellum Plays by Women: Contexts and Themes” in Richards and Nathans,

Oxford Handbook of American Drama, 115. Kritzer notes that “[a]pproximately forty women wrote plays that were published or performed in the United States”

during the antebellum period.

41. Jason published the novella

The Lime-Kiln Man in 1855, the title page of which describes him as “Author of ‘Kate Edwards,’ ‘the Two Friends,’ ‘The Convict,’ ‘My Cora,’

ETC.” See Jason C. Swayze,

The Lime-Kiln Man, or, The Victim of Misfortune (New York: DeWitt & Davenport, 1855). In the April 12, 1856, entry in his daybook, Jason mentions working on “my play of

The Gambler’s daughter.”

42. On

Venus Miscellany, see Donna Dennis,

Licentious Gotham: Erotic Publishing and Its Prosecution in Nineteenth-Century New York (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), chap. 5. While Dennis does not note Jason’s participation in the paper,

his mention of his work with “George Acarman [

sic]” on a “love paper” in the September 20 entry of his 1856 daybook and the listing of “Clarke” as one of the publishers of

the

Miscellany leads us to this conclusion.

43. Oscar Swayze, “Biographical Sketch of Kate Lucy Edwards” in Kate Lucy Edwards Swayze Papers, Kansas Historical Society,

Topeka, KS.

44. George C. D. Odell,

Annals of the New York Stage (New York: Columbia University Press, 1931), 7:125.

45. This estimate comes solely from the observation that Confederate general Stonewall Jackson did not acquire his nickname

until the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861.

46. The biographical information on Jason Clarke Swayze comes from “Jason Clarke Swayze,” in

The United States Biographical Dictionary: Kansas Volume (Chicago: S. Lewis & Co., 1879), 623–26; William E. Connelley, “Jason Clarke Swayze,” in

A Standard History of Kansas and Kansans (Chicago: Lewis Publishing, 1918), 4:1800–1801; and Richard H. Abbott, “Jason Clarke Swayze, Republican Editor in Reconstruction

Georgia, 1867–1873,”

Georgia Historical Quarterly 79, no. 2 (1995): 337–66. As Abbott notes, the Connelley essay is not entirely trustworthy, and indeed, much work remains

to be done documenting the interwoven careers of Kate Edwards and Jason Clarke Swayze.

47. Abbott, "Jason Clarke Swayze," 356, 359, 360.

48. Four years later, Jason Clarke Swayze was murdered in Topeka, purportedly for his newspaper’s coverage of a local lottery

scandal. Abbott, "Jason Clarke Swayze," 366. See also John W. Wilson and J. Clarke Swayze,

The Assassination of J. Clarke Swayze, and Trial of John W. Wilson, Containing Full Proceedings in the Trial and Acquittal

of Wilson, Together with Press Comments, Sketches, Articles from the Blade and Times and Matter Not before Published (Topeka, KS: Blade Printing Establishment, 1877).

49. Nathans,

Slavery and Sentiment, 107–9.

50. More specifically, we consulted the editions of

Inkle and Yarico included in Felsenstein,

English Trader, Indian Maid; and Barry Sutcliffe, ed.,

Plays by George Colman the Younger and Thomas Morton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983). Felsenstein took Elizabeth Inchbald’s 1808 acting edition of the play as his

copy text, adding a prologue that Colman wrote in 1789 and restoring songs omitted or shortened by Inchbald. Sutcliffe produced

an edition by attempting to reconcile a manuscript copy preserved in the Larpent Collection of Licensing MSS in the Huntington

Library with the first published edition by G. G. J. and J. Robinson, London, 1787. While the Felsenstein and Sutcliffe volumes

proved useful references, we found the 1825 edition matched “Sweethearts” most consistently.