Essays

The Common Pot

Editing Native American Materials

We beg leave to lay our concern and Burdens at Your Excellencies Feet. The Times are exceedingly alter'd, Yea the Times have turn'd everything up Side Down, or rather we have Chang'd the Good Times, Chiefly by the help of the White People; For in Times past, our Fore Fathers lived in Peace, Love and great harmony; and had every thing in Great plenty . . . And they had no Contention about their Lands. It lay in Common to them all, and they had but one large Dish, and they Cou'd all eat together in Peace and Love . . .—Mohegan petition, 1789.

Fifty years ago, it might have been reasonable to assume that a documentary editing project involved the correspondence of a great political or historical figure or the works of a literary master published in print volumes. As surveys of the current profession, however, have shown, this is no longer the case. A cursory glance at the "Recent Editions" section of any new Documentary Editing volume reveals, for example, works on women, families, artists, African-Americans, Native Americans, and several non-canonical authors in print and in electronic form. Such an evolution has prompted some introspection within the field, as articulated succinctly by past Association for Documentary Editing president Kenneth Price, "[W]hat is it that we should be editing, how should we go about it? how should we fund it? how should we position it within the disciplines?"[1]

In 2009, a panel at the annual ADE meeting in Springfield, Illinois, addressed these questions as they related to literary text.[2] In 2010, a similar panel convened in Philadelphia to explore the advantages and challenges of editing American Indian documents.[3] The following article elaborates on one such paper at that roundtable in Philadelphia and discusses in more detail the philosophical and practical choices we made as editors of the Yale Indian Papers Project, a cooperative effort by a number of institutions to publish a scholarly edition of New England Indian primary source materials.

Conceptualizing the Pot: Why We Edit

Recognizing that the materials that would comprise the edited collection involved multiple cultural groups and disciplines, we viewed the original manuscripts as a shared history, a kind of communal liminal space, neither solely Euro-American nor completely Native. Consequently, we adopted an inclusive philosophical approach influenced by the New England Native idea of a communal dish or "common pot" out of which many different people may partake.[4] The metaphor implied a certain strategy of accommodation in which many partners coexist cordially with different points of view. This seemed the best approach both to organizing the structure and arranging the scholarly apparatus of the project, but it also reflected our desire for the British and Native American scholarly communities—previously silent voices—to have a seat at the table as vital constituents.

A scholarly editing endeavor on New England Indians should not come as much of a surprise. There is hardly a lack of documentary materials. Indians have been part of the New England story long before that saga had began to be told by Europeans nearly four hundred years ago. Native contact with Europeans began in the sixteenth century, and New England Indian territory was one of the first, after Virginia, to be settled by English colonists during the early seventeenth century. Suffering decimating plagues, decades of warfare, and a harsh colonial land policy that disseized them of thousands of acres of their traditional homelands, New England Indians weathered the colonial period as subjects of the British crown, only to be considered as wards of the states in the new American republic. Nevertheless, New England Native peoples have survived for well over four hundred years, as have documents relating to their history and culture. Official reports from authorities in London; correspondence and financial accounts from colonial and state governments in New England; and petitions, memorials, and letters from Indians themselves to general assemblies are only part of a 400-year-old documentary record that still exists in various repositories around the world.

Yet, to the chagrin of many scholars, researchers, and tribal members, much of that record has remained unpublished and for various reasons practically inaccessible.[5] Individuals interested in using these manuscripts are required to visit a number of repositories across the United States as well as in other countries, where they may encounter conditions that can complicate the researcher's task—archaic or poor quality handwriting, or institutional restrictions on the use of worn and fragile manuscripts—making it time-consuming and costly to access these materials. For academics, the lack of a substantial body of resources has produced a stunted literature and an uneven academic discourse, where New England Indians are written out of the curriculum after a brief mention of the first Thanksgiving or of the end of King Philip's War of 1676. Moreover, complicating the historiography of New England Indian history, commentaries on that history, whenever they have been written, have been from the perspective of American historians including regional and local antiquarians, with little input of either Native or British scholars.

To the frustration of many educators and students, very little of the existing published primary documents on New England include materials about Native Americans, nor are those found on the Internet necessarily accurate, unbiased, representative, or complete.[6] For New England tribes, the lack of a substantive published archive of their history has led outsiders to form an incomplete historical awareness of them and has left the tribes wishing to have their story told as part of the national narrative.

For the general public, lack of access to such information has led to misperceptions of New England Native culture and sometimes a persistence of racist ideas. With books like The Last of the Mohicans still in popular consumption, regional Indians have fought the misplaced trope of the "vanishing Indian" for at least two centuries, resisting with a message of "We are still here." In 1992, Donald Trump told a Senate committee that one locally prominent federally recognized tribe of Indians "call themselves Indians, but they don't look like Indians to me." Statements like these motivated the political cartoonist Robert Englehart to publish what many Connecticut Native people felt was a disrespectful jab at their ancestors. (See Figure 1.) Several years later, a letter to the editor from an Oglala Sioux published in the Hartford Courant dealt another punch with a seemingly valid source implying that there were no Indians left along the northeastern coast of the country.[7] However false, the message began to gain some traction. The lack of a visibly documented past made attempts at erasure easier.

Figure 1: Robert Englehart, "The Golden Hill Paugussetts," The Hartford Courant, July 21, 1993.

The question of how to address these issues prompted a number of discussions between historians, ethnohistorians, and members of several of the New England tribal communities, out of which sprang the concept of a documentary editing project devoted to publishing original manuscript materials on, about, or by New England Indians. In 2003, the idea found a welcome home at Yale University's Department of History and American Studies Program and formally became the Yale Indian Papers Project.[8] At the outset, we had four critical goals: to publish materials that would give evidence of a continued Native presence in New England, to make those materials available at the least cost to everyone, to edit the documents with the highest professional standards, and to provide a balance of perspectives in the editorial process.

Our first challenge was to delineate our document corpus. Unlike many others, this project would not solely consist of the papers of one particular individual or be collected from one single institution. In fact, it would not even comprise the materials relating to just a single tribe. Taking into consideration the mobility of New England Indians, their historical interactions, their pattern of marrying outside their tribes, and general kinship relations forming a common link among tribes, we determined that we would include documents associated with Indians of the entire region of New England drawn from many different repositories. In doing so, we recognize that our editing agenda is challengingly but necessarily broad.[9]

This strategy has it rewards, however. For example, the Treaty of Hartford ended the Pequot War on September 21, 1638. In discussing the terms of the agreement, scholars for over two centuries have consulted, without questioning its authoritativeness, a copy of the document at the Connecticut State Library, which spells out six provisions governing future relations between the English colonists and the Pequot, Mohegan, and Narragansett Indians. A closer inspection of that manuscript reveals a remarkable discovery that no scholars have previously commented upon: it is a copy written more than a century after the original for a legal proceeding, and may be different from the original treaty, which, to our knowledge, has never been located. However, we did find a version composed in 1665, only twenty-seven years after the war, at the British Library in London.[10] It is torn and incomplete, but revealing. The first portion of the British version enumerates eight provisions before the tear in the folio, with the subsequent numbering on the second folio ending at fourteen, more than double the provisions of the "authoritative" copy.

Another challenge was to determine who our audience would be and how much we would need to adjust the standard editing apparatus to reach those users. Older scholarly editing projects on the founding fathers or on elite social figures such as Horace Walpole, for example, targeted an educated, scholarly, and cultured readership. They could leave text in French untranslated without much consequence. But our potential audience was much more diverse. Interest in the project came from tribal members, tribal elders, tribal historians, students and teachers at every level of learning, as well as academics from history, anthropology, ethnohistory, law, religious studies, and a host of related disciplines.

With the conceptual dynamic of a "common pot" approach in mind, we assembled a preliminary advisory board consisting of an anthropologist with years of experience in southern New England Native oral history, a British historian specializing in the seventeenth century, a nationally respected New England colonial historian, an expert in Native American legal issues, a Connecticut tribal archivist, a Connecticut tribal historian, and a curator of American Indian manuscripts. Additionally, we brought together a consortium of specialists on New England Indian history, ethnohistory, and imperial studies, consisting of American, Native American, and British scholars.[11]

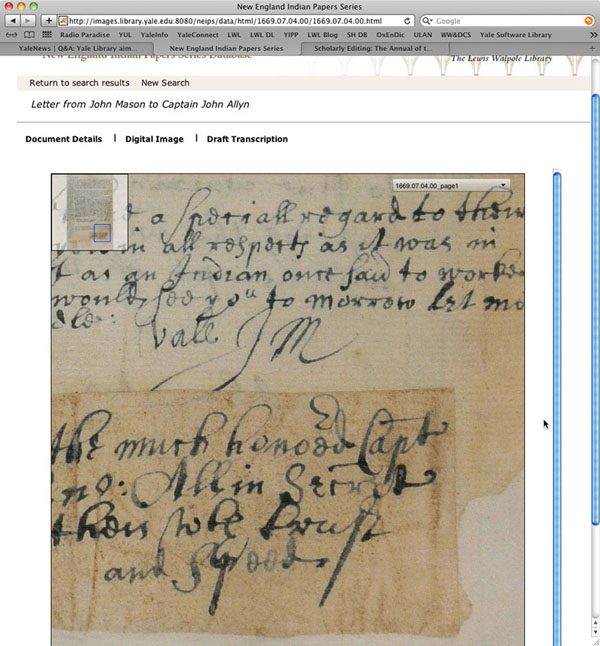

In trying to understand the needs of the Project's anticipated audience, our advisors suggested taking stock of the resources available and conducting informal surveys of numerous potential users of the edition. Again, the approach was meant to be inclusive. An exploratory committee asked faculty and graduate and undergraduate students in American studies, history, and anthropology from Yale and other universities, various New England tribal members, elders, and tribal historians, visiting scholars to Yale, British scholars, and history teachers from the Hartford, Connecticut, high school system what they would like to see in a Native-themed publication series. The overwhelming response of the surveys was that individuals wanted greater access to original materials. Access took different shapes. Some researchers wanted images of the documents, while others preferred to read transcriptions of the originals. A Native elder wanted both the image and a transcription that conformed to the image so he could read and understand exactly what his ancestors had put on paper. Surprised by the number of existing materials about her tribe, another elder wanted to know more about the Indians who had written or were the subject of the documents. Many academics suggested the annotations present various analytical interpretations of a document's contents if and when possible. We used these comments in shaping the Project's technological and methodological parameters.

Creating the Pot: How We Edit

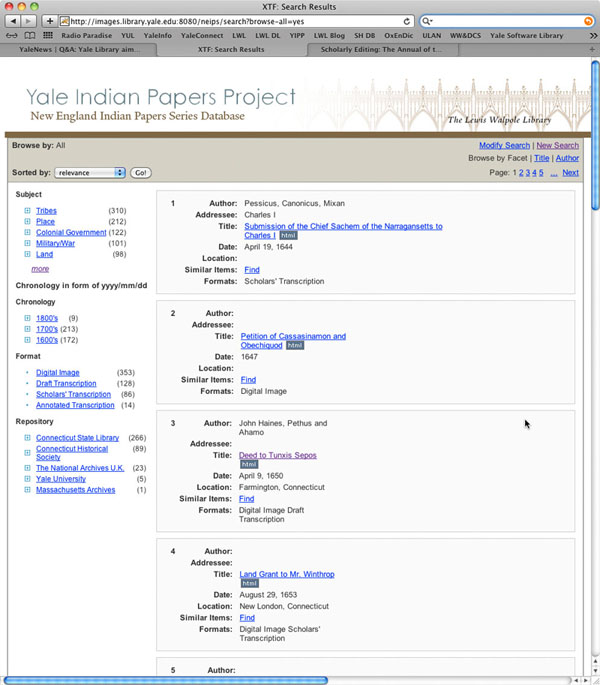

The ability to create and publish in a digital environment gave us the flexibility we needed to satisfy the requests of the researchers, the project's main stakeholders. We intend our web platform to be a research asset for those scholars who have a good sense of what they are looking for, but we also designed its browse and site research features to be an exploratory tool for those with less focused interests. We replicate physical access in an electronic world by providing high quality digital images processed through the Zoomify applet. For documents that are pasted into a book, we use a fiber optic light sheet to illuminate and photograph text that is hidden on the reverse side. Readers can pan through and enlarge the images to view fine detail and inspect imperfections. At the same time, we provided intellectual access to two forms of transcriptions—a typographical facsimile (called "scholars' transcriptions") with cross-outs, misspellings, and abbreviations intact,[12] and a TEI-encoded annotated version with regularized spelling and punctuation. Items are presently made available at no cost through an online web application called the New England Indian Papers Series Electronic Archive at www.library.yale.edu/yipp.

Individuals, places, events, and themes are searchable in a number of ways. A search engine provides readers with full-text searches of both the scholars' and annotated transcriptions. A robust browse feature uses current themes in ethnic studies, Native American/indigenous studies, history, American studies, law, and religious studies, as well as issues important to modern Native communities, such as land loss, land use, and the concept of sovereignty to increase intellectual access to the documents and encourage exploration into the topics at hand.[13] (See Figures 2 and 3.)

Figure 2: Browse features of The New England Indian Papers Series Electronic Archives database.

Figure 3: Enlarged image of document sample from The New England Indian Papers Series Electronic Archives database.

We provide multiple entries for each document's geographic point of origin and all other mentions of place within each item. One assigns them to current American towns, another to the American town that existed (if different) when the document existed, and still another to the Native territory or territories in which they also exist. For example, one can find the geographical landscape feature Cuppunnaugunnit,[14] once the designation of a Pequot Indian village, in the present town of Stonington, Connecticut. English colonists settled Stonington in 1649 as part of Connecticut, but from 1658 to 1662, it had been absorbed into the Massachusetts Bay Colony under the name of Southertown until reverting to Connecticut as part of that colony's charter. This brief diversion is important because during these five years, the village and the people who inhabited and moved through it were in a different jurisdiction and subject to different laws and control, an often-missed fact that could prove crucial to someone's research. Thus, Cuppunnaugunnit may be accessed though our hierarchical subject list under the following conventions:

- Place: North America: United States: Connecticut: Stonington: Cuppunnaugunnit

- Place: North America: Indian Country: Pequot Territory: Cuppunnaugunnit

- Place: North America: Colony of Connecticut: Stonington: Cuppunnaugunnit

- Place: North America: Massachusetts Bay Colony: Southertown: Cuppunnaugunnit

Furthermore, if a location is specific, such as a pond, hill, or discrete region within a town, we will enter the geographic coordinates in the form of longitude and latitude into the electronic archive's database and link them with a map to provide users with a geographic context with which to view locations referenced within each document. This additional layer of data will give researchers the ability to perform spatial analysis and may reveal patterns in territorial boundaries, settlements, or other forms of land use that might otherwise go unnoticed. These features create a landscape in which information is embedded. In pursuing this approach towards towns, lands, and landscape features, we borrow from the Native concept of land as a repository of cultural knowledge.[15]

In addition to geographical data, we create a biographical record for each individual, Native or non-Native, named in a document, regardless of rank or renown. In some instances, there may be an abundance of information on a person, such as the Mohegan sachem Uncas; yet in many cases, there is very little extant information regarding other individuals outside what is written in one particular document. Undeveloped biographical records can be augmented over the course of the Project. As a rule, for each individual, we provide, when known, the appropriate birth and death dates, nationality or tribal affiliation, aliases, genealogy, and a list of documents in the database in which that individual can be found. Also presented are the names of offices a person may have held (governor, captain, selectman, etc.) and include positions within Native governments as sachem, councilor, elder, or headman/woman. We further provide a short summary and relevant bibliography of the individual in question. For entries on non-Native persons, we tailor the information to include that individual's role in Indian affairs or connection to Indian tribes, making the whole entry different from the conventional biographical sketch or encyclopedia article.

The Project's web application features allow users to search for a particular individual by the role he or she plays within the document and to select all documents in which the particular individual's name appears as either author or recipient, witness or endorser, or is otherwise mentioned within the body of the document. Furthermore, we treat dates as a similar category of inquiry. Thus, researchers can search for documents created, witnessed, certified or recorded on a certain date, or locate all instances where a particular date or year is mentioned within document text. This is especially helpful to those examining extended land claims or researching the progress of certain legislation.

Even though much of our methodological process remains the same as that used by more traditional editorial undertakings, there are some challenges that raise the question of whether it is possible for the profession to establish a uniform set of guidelines for scholarly editing of multicultural or Native American material. For projects like the Yale Indian Papers Project, these include balancing cultural perspectives and allowing multi-disciplinary insights to enlighten our annotations, such that they do not rely simply on the study of history but equally on the fields of anthropology, archaeology, folklore, mythography, and Native and indigenous studies.

Consequently, we have developed a two-pronged strategy. As editors, we write document annotations to identify individuals, places, dates, and certain events, to clarify textual uncertainties, and when needed, to explain connections among related materials and put the document into historical perspective. To accomplish these tasks, we rely on our knowledge about New England Native Americans, our experience of working with Indian communities for over three decades, as well as our academic training. We provide helpful and perhaps critical information to the best of our professional and scholarly abilities, but we also recognize that we cannot speak for all the disciplines that have a stake in our work, nor do we represent the perspective of Native people themselves. Therefore, we provide a forum for these different voices by inviting a number of subject-specialist consultants drawn from within the stakeholder communities and from academia to write commentaries for a particular document or for a series of associated documents that would expand our initial explanations or extend the scholarly discussion into further analysis or debate. The consultants' annotations might include Native origin stories, oral sources, and traditional beliefs while also including Euro-American original sources of the same historical event or phenomena, thus offering two kinds of narratives of the past.

As an example of the utility of a multi-disciplinary approach, let us consider a passage recorded by Ezra Stiles in which a colonial woman recalls a family account of a Pootatuck Indian "powaws."[16] According to the testimony, when the woman's mother was a child, she saw a finely dressed Indian "Popoose Girl" being led between the Indian girl's mother and aunt during a ceremony "into the Body of the Indians." The mother and aunt, as the document describes it, later emerged from the "midst" without the Indian girl or their "Ornaments" and walked away "howling, crying, and lamenting." When asked what happened to the young girl that accompanied them, the two distressed women did not provide an explanation but only said that "they should never see that little Girl any more." From this, the English witnesses concluded that the Indians killed the Indian girl. When Stiles repeated the story years later, he used it as evidence that Indians sometimes offered human sacrifices at their religious ceremonies, a conclusion that no one has challenged since.[17]

However, after we shared the description of the above account with a Connecticut tribal elder, she suggested that the events described by the English attendees might have been a puberty rite-of-passage ceremony, after which the little girl passed on to another stage in her life, becoming a young woman. The mother and aunt, therefore, would no longer "see" the young girl because she had entered womanhood. We can explain the disappearance of the Indian girl during the ceremony through annotation saying that almost all Native American tribes had puberty ceremonies for young girls after their first menstruation cycle, during which the young women were isolated from the rest of the tribe. Should Native scholars or tribal members wish to elaborate on this alternative perspective, they are free to do so in an associated commentary essay.

We intend, whenever possible, to provide an opportunity for a variety of scholarly opinions through the commentary essays. Some may be provocative or controversial, others developing threads of a scholarly conversation rather than an argument. To that end, we have located the notes, papers, and correspondence of a number of individuals who have written or published on New England Indians in the past[18] whose comments on a number of documents within our collection may be enlightening or instructive, and we intend to include these materials both as individual items in the electronic archives and linked to the documents to which they are associated.

With respect to censorship, our document transcriptions are not censored for rude or improper language nor for political, religious, or racial sentiment. Offensive words and phrases are neither highlighted nor specially marked. Instead, we let the actual words of the original document reflect the era in which they were written. However, we are sensitive to terms that some may consider culturally offensive in the twenty-first century and will not replicate them in annotations or commentary. Nevertheless, because of the multicultural and multidisciplinary nature of the project, we are required to handle collections and materials that are not typically associated with other documentary editing projects (e.g., fieldnotes, photographs, cartographic materials as well as miscellaneous papers of archaeologists, anthropologists, ethnobotanists, and surveyors). In dealing with these materials, we are aware that we might encounter certain objects and information that New England Indians perceive to be problematic. For some Native groups, these include the publication of documents and materials containing detailed information about human burials and remains, sacred rituals, as well as ceremonies or spiritual practices. When we encounter such materials, as we did with the example of the Pootatuck powwow, we consult with the Project's Native advisors, or with the appropriate tribal representatives, to discuss how the project should approach the use of them.

Sharing the Pot: Continuing Challenges

The task of establishing professional editorial practices and a sound editorial policy for a documentary project can be an enormous undertaking, especially when the focus of that project diverges from the more conventional national icon-based undertakings. Calls to create uniform standards for editing Native American documents may remain unanswered because of the varying parameters of a project or the degree to which a particular project involves Native American materials. As just demonstrated, the Yale Indian Papers Project is designed to provide an inclusive approach to its organization, a culturally sensitive approach to its editorial policies, and a multicultural perspective to its annotations, but this strategy may not prove feasible for another Native-focused endeavor. Nevertheless, we still face challenges that may require consideration from within the wider editing profession. As Timothy Powell has explained in a recent article, some problems go beyond method and practicality and call for new models of thinking by the whole documentary editing profession.[19]

Editing a document on Indian leaders or about Indian people is, in fact, a fundamentally different act from editing one on George Washington, Thomas Edison, or James Boswell. Scholarly editing, as the profession currently practices it, is grounded in a Western, Euro-American academic tradition, the same tradition in which these three men operated. A Native American document, however, lives in two worlds, two cultures, and it is the responsibility of an editor to engage the Native community if his or her editorial endeavor intends to give its readers the appropriate Native perspective. One relationship model that we in the field, perhaps, should not perpetuate in accomplishing this task is the one so often employed by anthropologists in the late twentieth century in which Indians are treated less like collective partners in a process but more like subjects of inquiry, without agency or significance. Vine Deloria, Jr., describes the consequences of this professionally irresponsible behavior.

Over the years anthropologists have succeeded in burying Indian communities so completely beneath the mass of irrelevant information that the total impact of the scholarly community on Indian people has become one of simple authority. Many Indians have come to parrot the ideas of anthropologists because it appears that the anthropologists know everything about Indian communities. Thus, many ideas that pass for Indian thinking are in reality theories originally advanced by anthropologists and echoed by Indian people in an attempt to communicate the real situation.[20]Powell addresses this problem by contending that editors should let Natives speak for themselves, which means letting a narrative emerge from the community where, as one Indian scholar has put it, "the Native voice is present, persistent, forceful, helpful, and significant."[21]

Of course, there are other hurdles to consider: Establishing which Indian groups should be participants within a project—federally recognized tribal governments, state recognized tribes, tribal factions or unaffiliated enclaves—and then determining the proper spokesperson for that group may be a difficult process. Equally problematic are questions of tribal identities, competing tribal perspectives, ownership rights, and Native control over research activities. The Apache, for example, have adopted a policy to control "the misappropriation and unauthorized commercial and other use" of their cultural property. At a time when many tribes are revitalizing their culture, thorny issues of repatriation of manuscript materials may also arise.[22] However, it has been argued that freely accessible digital projects may actually solve many repatriation problems.[23]

One thing is for certain. The scholarly editing profession is on new ground. Just as editing Native American materials is fairly new and different for us, our profession is just as new and strange to many Native Americans. Clearly, Indians are at the door, but how we answer the knock will determine the fertility of this venture. We can see the threshold as a crisis or opportunity.

Notes

PDF

PDF