Encoding and Representing Repetition in Lyn Hejinian's My Life

Encoding and Representing Repetition in Lyn Hejinian's My Life

When she was thirty-seven years old, Lyn Hejinian wrote My Life, one of the best-known works to emerge from the Language movement with which she is associated. As autobiography, it challenges most conventions of the genre. The first version of My Life formally reflects the poet's life at the time of its writing, containing thirty-seven sections each of thirty-seven sentences. A revised edition, written when Hejinian was forty-five and containing forty-five sections of forty-five sentences is, then, both an expansion and a revision—it adds years to a life but also reflects the ways those years change the poet's perspective on what came before. As Hejinian notes in her essay, "What's Missing from My Life," the context of the later edition is doubled, as parts of the text date to the late 1970s and the Language writing scene of the Bay Area while others parts were born in the mid-1980s, a time that Hejinian describes as giving way "if not to despair then certainly to severer commitments, more sustained rigors." [1]

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a work that deals with the changes brought on by time, My Life has a somewhat complicated publication history. The first version was published in 1980 by Burning Deck. A revised forty-five-section edition was published in 1987 by Sun and Moon and later reprinted in 2002 by Green Integer. In 2003 Shark Books published a continuation of the project, My Life in the Nineties, consisting of ten new sections, and Wesleyan University Press has recently published My Life and My Life in the Nineties, an edition that brings together the forty-five-section revised edition with the 2003 continuation. Additionally, Hejinian published an essay, "What's Missing from My Life," in 2009, which contains an expanded, sixty-eight-sentence version of the ninth section of My Life. The digital edition presented here includes the text from the original Burning Deck edition and from the Green Integer republication of the Sun and Moon edition. "What's Missing from My Life" is included here as supplementary material.

This tangled web of editions seem appropriate for a work that, like much writing of the Language poets, is interested in textuality and the many ways that words can converge and diverge. Throughout My Life, sentences repeat themselves, sometimes identical to their last appearance and sometimes slightly changed. The phrase "A pause, a rose, something on paper" floats through the texts, echoing both its previous occurrences and also Stein's "a rose is a rose is a rose." Sometimes the phrase appears on its own; at other times it is embellished, as with "A pause, a rose, something on paper implicit in the fragmentary text." [2] If one consequence of these motifs is to thematically stitch together a written life, another is to remind readers that each time they come upon a repeated phrase, it has already changed because so have they. Thus, My Life reminds one that reading is both material and phenomenological. As Hejinian notes, "Thinking about time in the book, it is really the time of your life." [3]

In this context, repetition—both within and between editions—becomes a complicated matter that raises questions of method when creating a digital edition that brings together multiple versions of the work. Traditional approaches to editing have tended to view repetition and variation in relation to the processes of writing, revision, and publication. Viewed from the position of any of the schools of scholarly editing that produce a single reading text—that of Fredson Bowers, [4] for example—these patterns within and across versions are either variants to be collapsed or higher-level aspects of the text that are more properly addressed by literary critics. Similarly, for editors such as Donald Reiman [5] or Peter Shillingsburg [6] who argue for the presentation of multiple versions of a work, the understanding of the patterns between and within these versions has been a goal largely left to an edition's readers. And while digital systems for presenting multiple versions of works—such as the Versioning Machine [7] —often give readers tools to view matching sections across versions, this experience is determined in part by theoretical and technical constraints. For example, when using TEI to encode multiple versions of a work, the convention is to call out not what stays the same but only what changes (see Figure 1). As Tanya Clement notes, choices of encoding depend on the editor's conception of the textual event, [8] and in this context applications of TEI can often be seen as corresponding with conceptions that focus on editing and emendation, aligning with the goals of traditional scholarly apparatuses.

<l n="3">Far

<app>

<rdg wit="#t7989-1-1">above</rdg>

<rdg wit="#nocturne_poems">away</rdg>

</app>

, stars wheeling in space,</l>Figure 1: An example, taken from the Versioning Machine documentation, of TEI encoding using the parallel segmentation method. As is common with TEI encoding, text that remains the same between witnesses (here, "Far" and ", stars wheeling in space") is unmarked.

Representations of repetition and variation, then, hinge on theoretical positions, standards of encoding and systems for visualizing an eventual edition. For example, while editors using the TEI's location-referenced method of encoding variants can indicate that a section from one version is repeated multiple times in another, many current systems for visualizing this encoding are unable to indicate all repetitions, especially for a long text or for an edition that includes nontextual versions. For example, in recent work to update the Versioning Machine to support aligning audio and text versions of a work, we encountered a performance by Spalding Gray in which the speaker repeats sections of a script several times (see Figure 2). Because the technical limitations we worked under make it difficult to indicate or highlight multiple sections of one audio file, the editor of the edition, James Sitar, was forced to choose an audio section to be considered as the principal repetition of the text, the one with which a user of the edition would be presented. While the sections of the versions in the Spalding Gray edition do not have simple one-to-one relationships, they are presented as such, reducing the edition users' access to patterns that are important to the text.

[Click on image to enlarge] Figure 2: Three versions of an excerpt from Spalding Gray's Swimming to Cambodia. Highlighted sections indicate repeated material. While the left and center columns represent text versions (a book and set of performance notes), the right column represents the audio from a performance. Due to technical limitations, the sections that are repeated in the text versions are linked with only one section in the audio version.

This kind of elliptical performance, in which sections of text are returned to again and again, highlights the ways traditional conceptions of textual editing trouble the creation of a digital edition that brings together multiple versions of My Life. As I argue below, the repetitions and variations in Hejinian's work are not merely editorial but also purposefully experiential. Similarly, Jerome McGann points out that texts are not two-dimensional but n-dimensional—they exist in relationships more complex than they are often given credit for, and the question for editors is how to mark or encode this dimensionality. [9] While an edition of the work based on traditional methods of encoding difference might shed light on the evolution of the text, I present instead an edition that, based on repetition and variation, focuses on the experience of reading. Below, I first introduce Hejinian and the Language movement, paying particular attention to their treatment of repetition and variation. I then describe the methods used in constructing the digital edition presented here.

Hejinian and the Language Movement

Hejinian is generally cited as one of the founding members of the Language movement, a group of poets who in the 1970s were largely based in the San Francisco Bay Area and New York City. Other poets associated with the group include Rae Armantrout, Charles Bernstein, Carla Harryman, Steve McCaffery, Bob Perelman, Leslie Scalapino, and Ron Silliman. Much of the loosely organized group's early writings were published in journals edited by members of the movement, such as This (edited by Robert Grenier and Barrett Watten from 1971 to 1973 and by Watten from 1973 to 1982), L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E (edited by Bruce Andrews and Bernstein from 1978 to 1982) and a newsletter, Tottel's Magazine (edited by Silliman from 1970 to 1981).

While the Language movement has produced writing in a wide range of styles, associated writers share an opposition to narrative as well as to straightforward representation and personal expression, preferring instead to experiment with syntax, structure, and the materiality of language. In perhaps the first use of the term, Silliman in 1973 introduced a selection of poems in the journal Alcheringa as "language centered," further describing them as "minimal" and marked by "non-referential formalism," although he concludes that the pattern he points out is "not a group but a tendency in the work of many." [10] Marjorie Perloff describes typical output from poets associated with the movement as giving the impression that "Swinburne or Crane have somehow been put through the Cuisinart: what finds its way into the bowl looks, at first sight, like so many chopped and hence unrecognizable vegetables." [11]

In addition to representation, poets associated with the Language movement have also questioned the status of the poetic speaker. While the movement has often been linked with the Black Mountain poets and the New York School due to some members' adoption of vernacular language, the goal of this language is generally not, as with these former movements, to present an authentic self but instead to create sutures in the text that bring the reader to recognize the constructedness of any voice, as with Bernstein's "Anyway / relationships—so so—we / you, distantly, when / wonder at that gap / in time." [12] While "so so" might in other contexts point to an authentic speaker, Bernstein's text swerves on to other registers, creating instead a self-conscious collage of voices. Multiply authored works by members of the group have a similar effect, as Watten has pointed out in relation to Hejinian and Harryman's novel, The Long Road, written together over twenty years, and Legend, a collection of pieces authored by Andrews, Bernstein, Ray DiPalma, McCaffery, and Silliman, in various combinations. [13] As undifferentiated mixtures of voice, these multiply authored texts point out that single-authored works, as well, lack the unitary voice and vision that the Romantics, for example, sought.

Much work from the Language movement similarly crosses and blurs the boundaries between existing forms and genres. For example, Bernstein's "The Artifice of Absorption" is an essay on poetics that is presented as verse, and Silliman describes his book Ketjak as a single poem composed of four works, one of which is itself a book-length poem.

Hejinian's My Life straddles similar lines. It seems to proclaim itself an autobiography but then refuses to present a coherent story of a life. Taking the form of prose poems, it both does and does not look like we expect an autobiography to look. And despite its lack of lineation, it often reads like lyric poetry, swerving from narrative vignettes ("They had ruined the Danish pastry by frosting it with whipped butter") [14] to observations ("It is hard to turn away from moving water"), [15] theory ("Idea 13.779: the same insanity of the invariable person"), [16] and aphorisms of dubious origin ("The mind has the message"). [17] Rather than the linear progress that is expected from autobiography, Hejinian puts before the reader a path that is always wandering, indulging in exploration or looping back on itself to revisit what has come before.

For example, both the 1980 and the 1987 editions of My Life contain eighteen occurrences, sometimes with slight variation, of the phrase "A pause, a rose, something on paper." The reader is told, "There is a pause, a rose, something on paper," [18] "There was a pause, a rose, something on paper," [19] as well as the more suggestive "A pause, a rose, something on paper implicit in the fragmentary text" (emphasis added). [20] Hejinian claims that such repetition "challenges our inclination to isolate, identify, and limit the burden of meaning given to an event (the sentence or line)." As in Stein's "a rose is a rose is a rose," toward which Hejinian's phrase nods, repetition functions not to corner and pin meaning but instead to call the reader's attention to the way each iteration, however similar, is not identical to the next. [21] Indeed, Hejinian's phrase points to the slipperiness given to Stein's rose by its existence "on paper." Material variance is, after all, a way one "rose" may differ from another, a kind of logical puzzle that Hejinian references with her question, "When you say, they are both reading the same book, do you mean the same writing but in different copies or do you mean in turns at the same copy." [22]

This kind of play is a staple of the Language movement. When Hejinian writes "Between plow and prow," [23] we might, for example, wonder if she is finishing an implied riddle that begins, "What is the difference between . . ." The answer, of course, could alternately be a letter of the alphabet, the shape of the letter "r," or the sound formed in air when one consonant is substituted for another. It could also, of course, be little, as the coincidental spelling slip leads to a realization that the physical forms of farmers' plows and boats' prows are, in fact, similar, as the two objects move through waves made of water or soil.

Writing of Stein's Melanctha, Perloff links this kind of affinity for repetition and troubling of sameness to theories of subjective experience and identity, claiming that Stein seeks to "show how a relationship, any relationship between two people who are at once the same and different, evolves. This is why repetition is essential. The composition must begin over and over again; the same words . . . and the same sentences are repeated with slight variation, and gradually everything changes." [24] Rather than insisting on meaning, repetition erodes the possibility of knowing the meaning of a word or the true nature of a person. Unlike realist authors, who pile on details as a way of trapping and presenting reality, Stein and Hejinian pile on repetition precisely as a way of exposing reality and the self as always overdetermined and open to a reader's situated perspective.

Often read in the context of feminist autobiography, My Life makes these claims regarding identity a central concern. Notably, Juliana Spahr situates Hejinian in relation to feminist autobiographers Gloria Anzaldúa and Maxine Hong Kingston, maintaining that while Anzaldúa and Kingston claim stable, although multiple, subject positions, Hejinian claims an unstable, shifting multiplicity and creates a text that "confronts head-on the constructed reality of autobiography and the reader's seduction by this construction . . . call[ing] attention to the methods by which the autobiographical subject is constructed by both author and reader." [25] Hejinian has written explicitly about this aspect of her work, claiming that "My Life purports to be about the social (and linguistic) construction of a person's life and hence about cultural placement." [26] Similarly, Hejinian is elsewhere insistent on the role played by the reader in constructing a text, and her descriptions of the "open text" argue for writing that, like My Life, "invites participation, rejects the authority of the writer over the reader and thus, by analogy, the authority implicit in other (social, economic, cultural) hierarchies." [27]

This oscillation between poetics, the personal, and the political is common with poets associated with the Language movement, for whom liberation is often understood through form. In this way, politics is not represented but enacted, and the formal device of the repeated phrase functions for Hejinian in this way, as an invitation to the reader to step into the text and question the experience of reading what has already been read. Considered in this light, each of My Life's repetitions is a chance to rewrite and reread identity—of Hejinian as autobiographer, of the sentence as unit of meaning, and of the reader as a participant in the creation of meaning. The constructedness revealed by repetition halts the otherwise relentlessly paratactic text and opens a space for the reader to question the text's construction of identity. This delicate balance relies on the rhythmic return of already encountered segments of text coupled with the constant possibility and worry that identity has not been perfectly preserved—that the reader does not remember what has come before or is in some way being tricked by the passage of time.

When, then, in the twenty-fifth section of the forty-five-section version of My Life, the repeated phrase returns as "A pause, a rose, something on paper, of true organic spirals we have no lack," the "organic spirals" mentioned might be thought of as a kind of symbol for Hejinian's evolving work. Rather than artificial spirals, which, perhaps, return again and again to the same point, organic spirals return to points that may exist as part of a set but, like a lineup of Dalmatians or identical twins that have experienced divergent lives, exhibit only an illusory identity that gives way to individual difference. David Jarraway notes this double function of Hejinian's spiral, noting how repetition in the text serves to both encourage metaphorical meaning while at the same time propelling the reader toward ever more associations, as "metaphorical identity . . . must give place to metonymic difference." [28]

This tension is found not just within each edition of My Life but also across the various editions, as sentences read in one edition appear in another, always hinting that either they have changed or the reader has. Indeed, between the two main editions, many sentences do change and in many ways. Some changes are minor corrections ("camelias" becomes "camellias"), [29] but others more clearly show the passage of time, as "The postman became a mailman" is amended, in the later version, to reflect contemporary language use and politics: "The postman became a mailman and now it is a carrier." [30] Others are tricks or strange slips that highlight the difficulty of delineating purposeful editing from copy-and-paste errors or mirages of the mind, as the clever phrase "The dictionary presents a world view, the bilingual dictionary doubles that, presents two" becomes, in the later version, the pause-causing "The dictionary presents a world view, the bilingual dictionary presents a world view, the bilingual dictionary doubles that, presents two." [31]

Indeed, one of the benefits of comparing the two versions of My Life that are presented here is a realization of the way the later version explicitly addresses these theoretical issues. In the thirty-ninth section of the later version, for example, Hejinian writes, "My life is as permeable constructedness." She follows this up, thirteen sentences later, with the phrase "Permanent constructedness." [32] Change, Hejinian implies, does not occur once or in one direction; it is instead permeable, shot through with contexts that belong to both the writer and the reader. Similarly, the construction of identities and texts is permanent, with time prompting constant reevaluation.

Perhaps more than other works that exist in multiple versions, My Life rewards consideration not as a text that has evolved toward a final form but as a work that lives an ongoing life. While it could be represented as some kind of authoritative edition or as a series of texts marked by editorial difference, it might also be represented as it is experienced: as a series of repetitions and variations, none of which are self-identical and all of which have the potential to send the reader spinning off through the larger work. In the next section I describe the methods used to create an edition based on these ideas of repetition and variation.

Approach

As noted above, the experience of a digital edition is constrained by the standards with which the text is encoded as well as by the system that will be used to visualize this encoding for a user. The conventions that surround encoding in TEI, both technical and social, have largely been built up around the encoding of editorial difference, perhaps for eventual presentation in a system like the Versioning Machine. For this reason, the method I've adopted for this project largely starts from scratch, avoiding standards like TEI and preferring instead to use simple data formats like CSV (comma separated values) that take little effort to construct and can be transformed in a variety of ways. While this decision removes some semantic information that would be retained had the texts been encoded in TEI, I want to use the edition as a way to consider the value in exploring alternative methods and the subsequent experiences for users of digital editions that emerge from them. Similarly, the decision to encode the texts used here in a format other than TEI might, I suggest, be seen as a way to historicize the adoption of that format in relation to editions that bring together multiple versions of a work, reminding the reader that Reiman's original argument in favor of "versioning" was based not on archival integrity or interoperability but on the time and money that could be saved by creating editions using photocopiers. [33]

The decision to use CSV as a base format for this edition is purposefully heterodox. It may also be, as a reviewer of this introduction pointed out, beside the point: a text encoded in TEI can always be transformed into a simpler format. However, my argument is not that simpler formats should replace more robust methods of encoding or that any specific format should become standard. Rather, I'm interested in exploring how encoding formats entail choices related to the construction of editions, how TEI has grown into a format tied, in multiple ways, to certain methods of interpretation and presentation, and how CSV introduces alternative ties. It is far easier to compare the sentences in a CSV file, for instance, and the output of that operation suggests further transformations and visualizations. By attending to such details, I intend to argue for a diversity of methods that might better respond to the specificities of individual texts. To the extent that Hejinian's My Life exhibits certain formal quirks that highlight the editorial choices discussed here, it becomes a useful test case for understanding the interweaving of texts, formats, people, and tools that comprise contemporary editorial practice.

The edition presented here was constructed as follows.

- The texts from both editions of My Life were first transformed into a single CSV file, essentially a list of all the sentences that would appear in the edition. While this method of encoding leaves out metadata such as section breaks, the formal constraints unique to Hejinian's text allow these features to be reassembled when the edition is reconstructed.

- Python's ngram.compare function was then used to calculate a score representing the difference between each sentence and every other sentence, such that identical sentences receive a score of one and sentences that theoretically have no similarity receive a score of zero. This method of calculating similarity is commonly used, and the edition shows it to be effective at identifying the repeated motifs in the text.

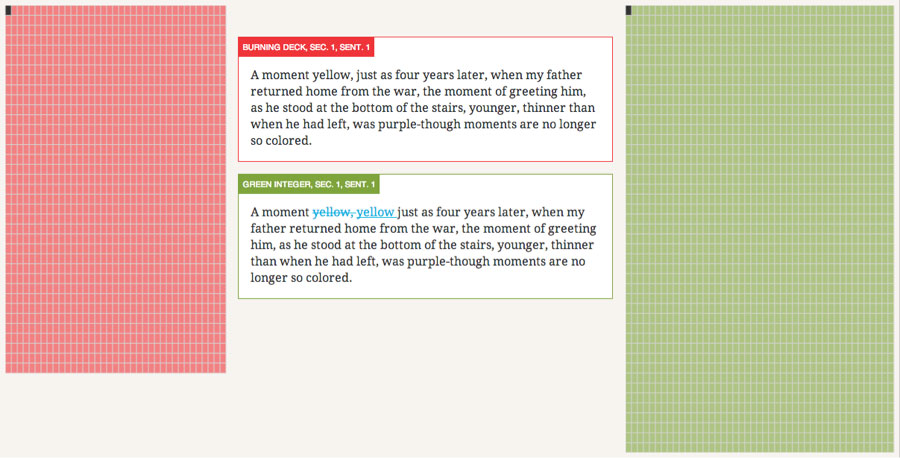

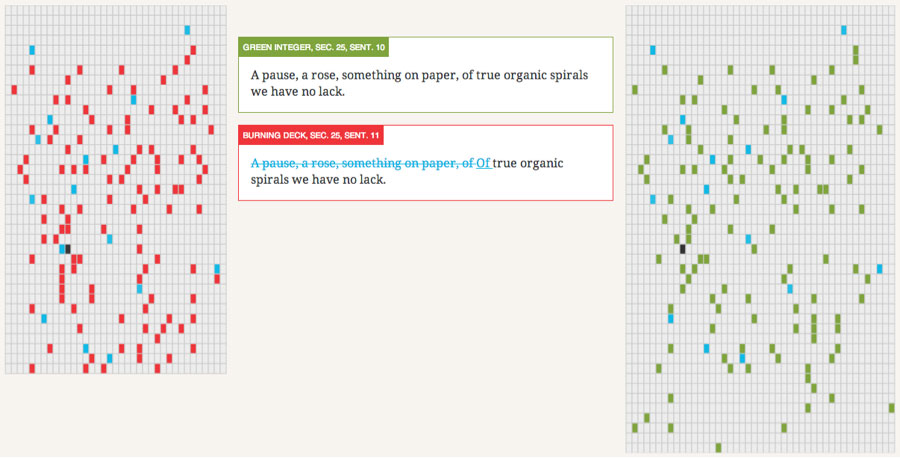

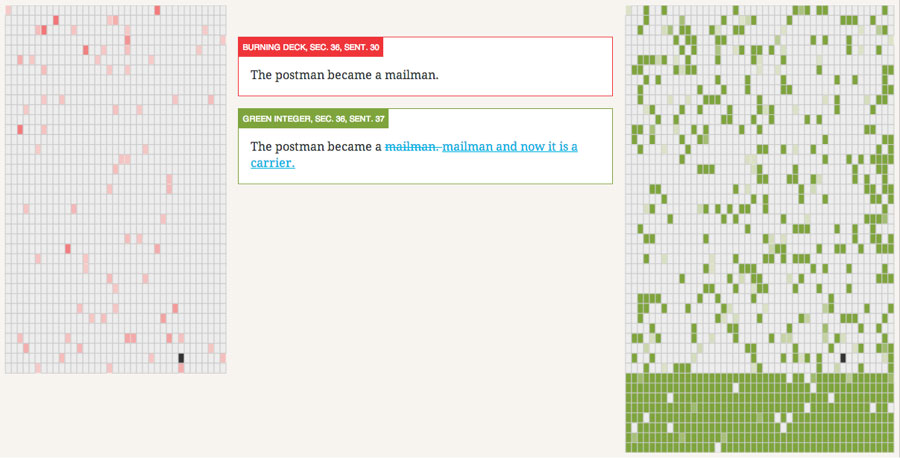

- The logic for the digital edition, written in d3.js, uses the list of sentences and the scores for their relations to visualize the two versions as grids of rectangles, one for each sentence and arranged according to the sections in My Life. Thus, the grid representing the 1980 Burning Deck edition consists of thirty-seven rows of thirty-seven rectangles, and the grid representing the 2002 Green Integer reprint of the 1987 Sun and Moon edition consists of forty-five rows of forty-five rectangles. Clicking on individual rectangles highlights the corresponding sentence in the other version (if applicable) and brings up the text of both sentences with their differences highlighted. Rather than determining matching sentences manually, the edition uses the computed relation scores to determine if a match is found, and these scores are also used to highlight in blue similar sentences found throughout the versions, giving users a way to view the variations of phrases that repeat throughout the work. Similarly, users can choose to view a representation of all the differences between the versions as well as all the repeated phrases. Again, these functions rely on the computed relation scores, with a manually defined cutoff for what constitutes a repeated phrase.

[Click on image to enlarge] Figure 3: A representation of the two versions of My Life included in this edition. Each version is represented as a grid of rectangles, with each row representing a section and each rectangle representing a sentence. Thus, the red grid to the left represents the thirty-seven-section Burning Deck edition and the larger green grid to the right represents the expanded forty-five-section version. Clicking on a rectangle displays the text of the corresponding sentence, with highlighted differences between versions, if appropriate.

[Click on image to enlarge] Figure 4: A representation of repeated patterns between the two versions of My Life included in this edition. Blue rectangles indicate variations of "a pause, a rose, something on paper" throughout the texts.

[Click on image to enlarge] Figure 5: A representation of the differences between the two versions of My Life included in this edition. The amount of change is represented by opacity, with lighter-colored rectangles representing minor changes. The area at the bottom of the right grid represents the sections added in the later forty-five-section edition. Uncolored rectangles in that area represent sentences that are repeated from elsewhere in the text.

Acknowledgments

I'd like to thank Lyn Hejinian and Brian McHale for their generous input and feedback on this edition. I'd also like to thank Lyn Hejinian and Wesleyan University Press for giving permission to use the text of My Life in this edition as well as Lyn Hejinian and Barrett Watten for their permission to reprint "What's Missing from My Life."

Notes